Coming of age in the pandemic has been rough on a generation of teens. The pre-existing mental health crisis, intrusive social media, and real existential threats like gun violence and climate change, on top of normal developmental processes, have made for a perfect storm. How are teens faring, and how can they be supported in this new milieu? New guidance is emerging from science, practice, and policies.

WHAT DO WE KNOW?

The pandemic touched every area of life.

The impact of the pandemic affected every important area of young people’s lives across the age spectrum, according to a March 2023 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.[1]

Academic achievement suffered, especially in reading- and math- related subjects. School engagement was often difficult: Enrollment declined, absenteeism increased, and some children lacked access to virtual education. Parents, who under normal circumstances would have supported children’s learning, were themselves deeply stressed, especially those with young children, and some families were overwhelmed by financial hardship, food/housing insecurity, illness and loss. Many educators met the moment with ingenuity and passion, but others suffered high rates of anxiety and burnout, and many left the profession.

photo credit Shutterstock MikeDotta

Young people’s physical health suffered, too. Though children were less likely to experience severe COVID-19 disease, a meta-analysis confirmed that they had increased risk for multisystem inflammatory symptoms, and 25% of children and teens who were infected with the virus got long COVID—namely prolonged mood disturbances, fatigue and shortness of breath, sleep disorders, loss of smell and taste, and fevers. Infected children’s rates of diabetes increased, and children’s health was more generally undermined by interrupted preventative care: Kids missed routine vaccinations, blood lead screenings, vision screenings, and dental care.

The pandemic’s toll on young people’s psychological wellbeing was uneven, but where it had an impact, it was intense and sometimes devastating. More than 265,000 young people lost a parent or caregiver to Covid-19, with Native American, Black, and Latinx children being two to four times more likely to lose a primary caregiver than white children. On almost any measure, impacts of all kinds were more acute for ethnic minority youth, low-income youth, LGBTQAI+ youth, and special education students, with their symptoms continuing to persist at higher rates.

photo credit Shutterstock Bricolage

Psychological impact varied by developmental period.

Stress affects children and teens differently depending on their developmental status and what they need from their environment. Those differences can be seen in the way the pandemic impacted young people:

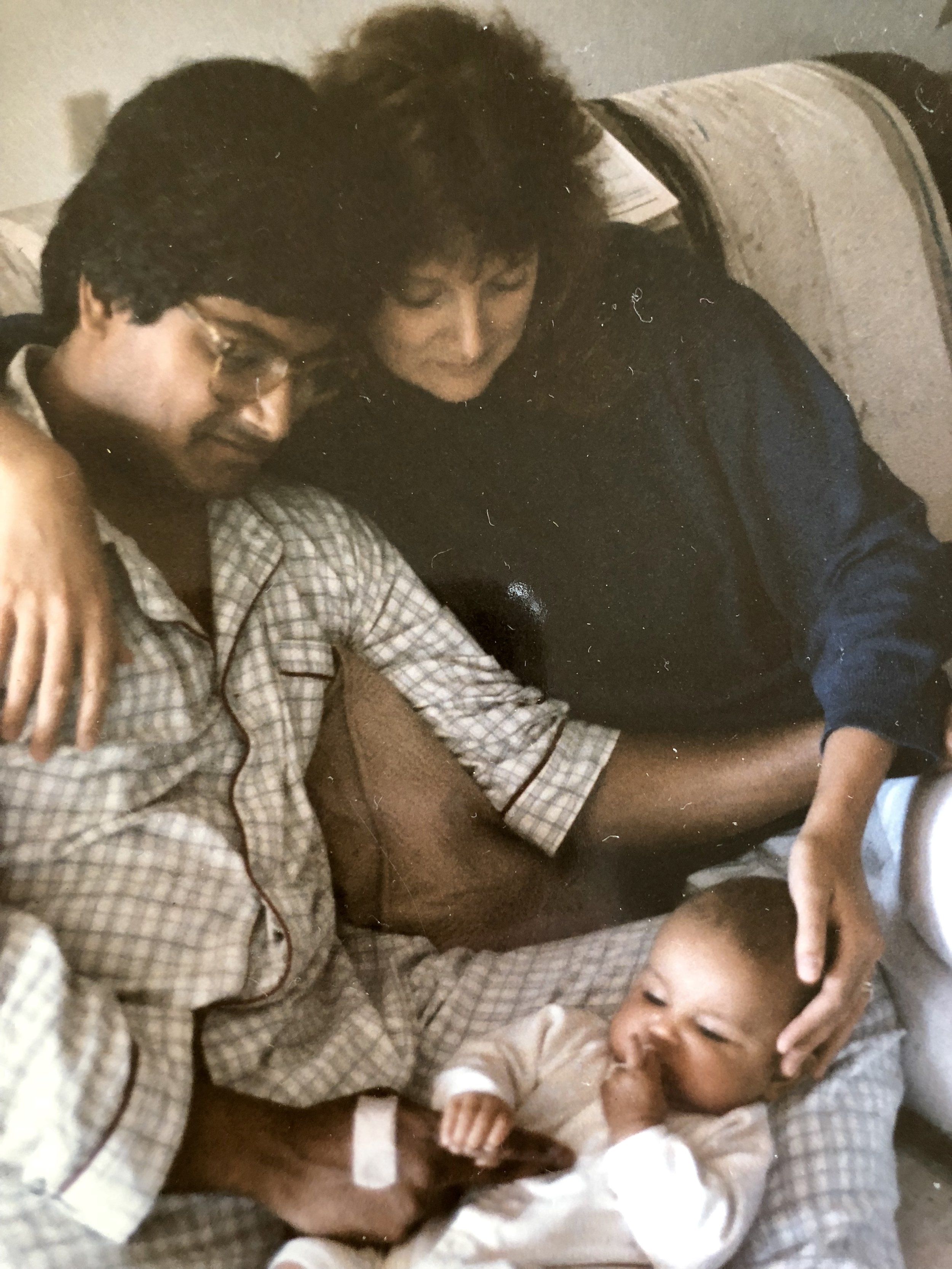

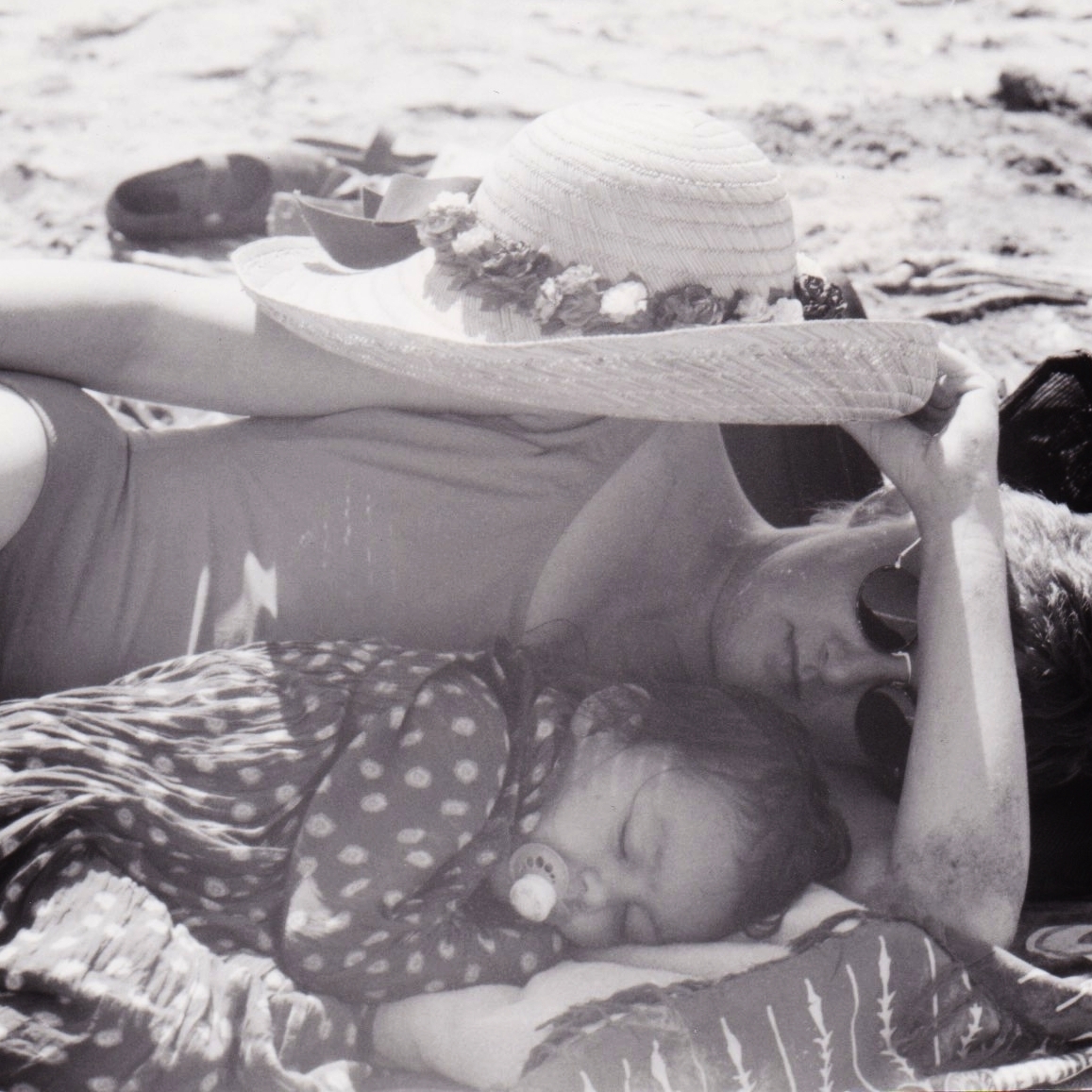

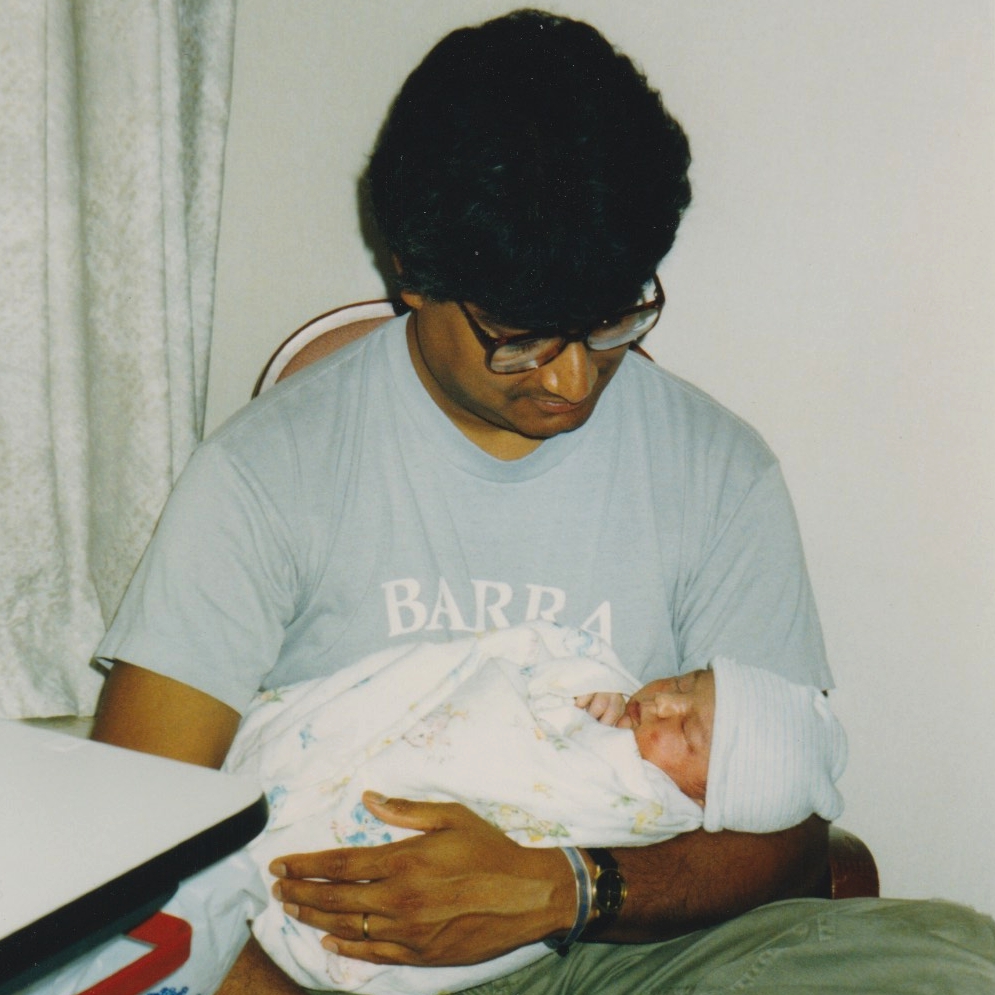

Babies. Studies of babies born during the pandemic showed that while they didn’t seem to be harmed by exposure to the virus in utero, exposed and unexposed babies alike showed developmental delays by six months, especially in areas of gross motor, fine motor, and social and emotional development. Why? Babies need responsive and attuned attention, with a serve-and-return style of interaction. During the pandemic, rates of anxiety and depression in parents and caregivers nearly quadrupled, making it difficult to provide the normal emotional “nutrition” babies need to develop well. Early intervention can easily recover these lags, but ignoring the impact can have lifelong consequences.

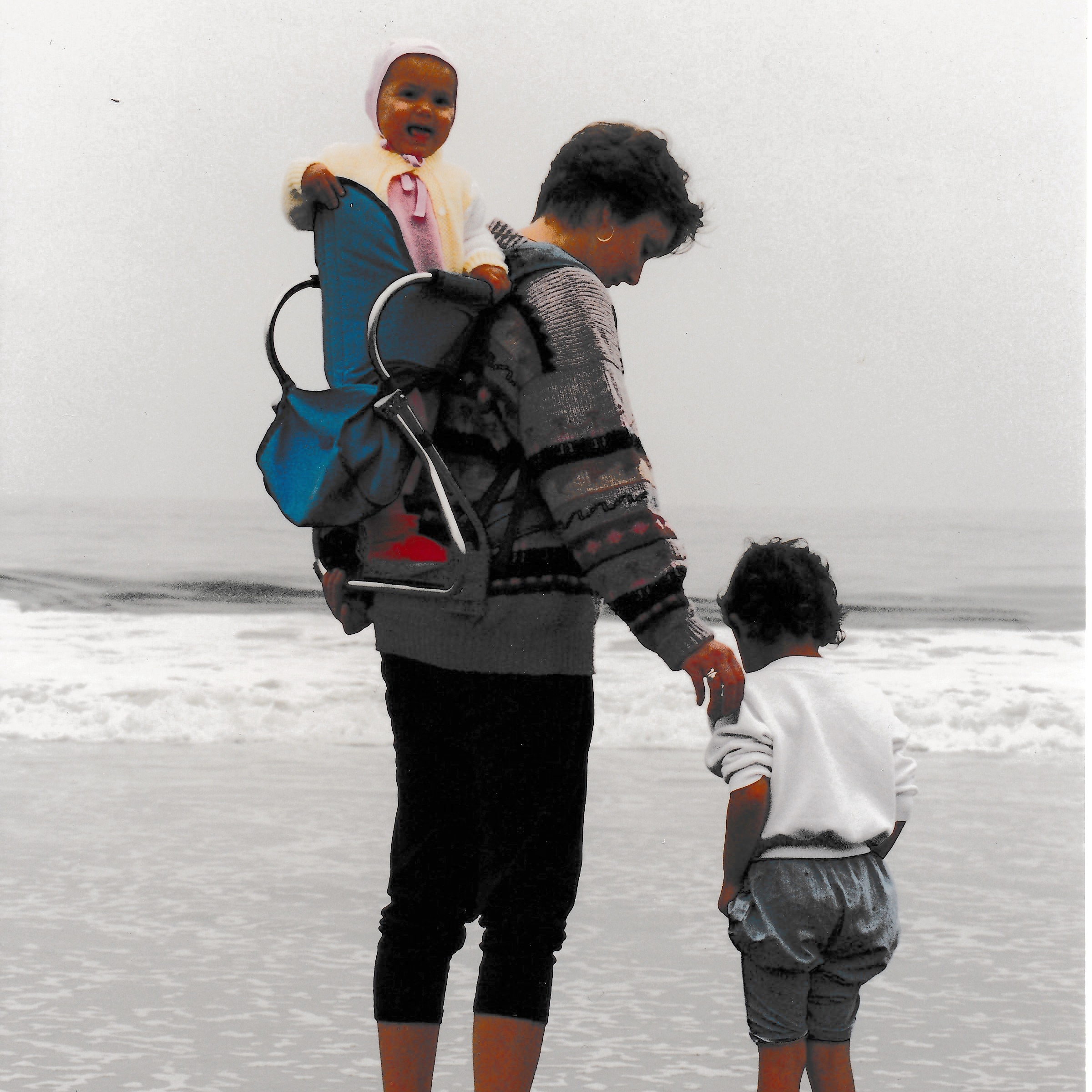

Young children. A report synthesizing the findings of 76 high-quality studies on the pandemic and early childhood showed that preschool enrollment declined, and early learning in pre-literacy, math, and social-emotional skills declined with it. Nearly half of parents of children under five said they were worried about their children’s isolation and restricted social development during lockdown. This is a valid concern, since peer engagement helps children develop social coordination, communication, and peer play. Parents reported higher rates of behavior problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems in their young children, compared to reports from previous years. The problems were more intense in families with more hardships, and on days when school or care was disrupted, highlighting the need for stability and routine.

During the pandemic, anxiety and depression rose in school-age children, along with increased rates of ADHD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and tics. Children ages six to 12 were more emotionally dysregulated; they exhibited more “internalizing” issues (e.g., withdrawal, low self-esteem, eating disturbances) and “externalizing” behaviors (e.g., agitation, conduct problems) compared to pre-pandemic rates.

In private conversations, several educators estimated to me that children are about two years behind in in their social skills; among other things, they’re having difficulty managing themselves and their emotions with their peers on the playground. Bay Area therapist Sheri Glucoft Wong reported that families are having a harder time organizing and coordinating themselves and making transitions as schedules fill up once again, a kind of real-world wayfinding problem seen in college students, too.

Teens. The pandemic poured fuel on the fire of the youth mental health crisis that’s been brewing for over a decade. Last fall, medical experts recommended that all children eight and older get screened for anxiety and that all teens get screened for depression. In March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report showing that youth mental health was still worsening, particularly for female, LGBTQAI+, and Black students, all of whom are experiencing more violence, distress, and suicidality. Six in ten female-identified students reported feeling “persistently sad or hopeless,” and sexual assault rates rose, especially for female students, LGBTQAI+ students, and American Indian and Alaska Native students.

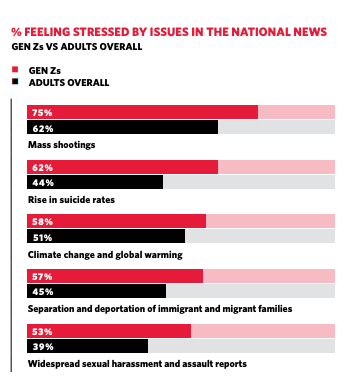

Children and teens worry about real events that are going on their lives, and the content differs by life stage. Young teens report in surveys that they worry most about their immediate experiences—e.g., school and friendships—while older teens worry about their future and the world they will enter. For about a decade, teens’ top worries have been gun violence and climate change. Many young people feel lonely and isolated; they feel that no one notices when they’re worried and that there’s no one to turn to for support.

Emily Frost and Quetzal François facilitate Bay Area mentoring and rites of passage program Love Your Nature for girls ages 10-20, nearly half of whom are BIPOC and/or queer- or nonbinary-identifying. I spoke with them about what they’re seeing in teens.

First, younger teens are worrying about their parents in new ways. “They’ve always been aware of their parents’ yelling or fighting,” Frost told me. “But now they’re overhearing their parents on the phone, late at night, discussing serious life decisions and struggles. Parents are stressed, so they’re less filtered, and teens feel scared about what they’re hearing. They’re also afraid to turn to their parents with their own problems because they don’t want to be an extra burden.”

In normal circumstances, young teens would begin individuating, i.e., seeking greater psychological autonomy while maintaining their connections. In typical individuation, young teens need to take their parents’ availability and stability for granted in order to push out; they might even create more conflict in order to practice gaining a separate mind. But it’s very challenging to individuate from someone you’re worried about, or have to take care of. And in lockdown, not only were young teens stuck in the same physical space as the adults from whom they were individuating; they were also cut off from access to the non-parental people—primarily their peers, but also mentors, teachers, and coaches—they needed in order to individuate.

Older teens in Frost and François’ groups, who are poised to launch into adulthood, express an acute sense that their future is uncertain. In stable situations, adolescents are designed to rush into the future—they’re creative risk-takers who excitedly move with their peers, their generation, toward what’s new and interesting. But these teens have deeply experienced losses of things they’d taken for granted—loved ones dying from COVID-19, school closures and the elimination of their educational and social worlds, and even disappointing college admissions that seem to be increasingly selective. Add to that a sense of impending doom about the climate crisis, gun violence, and health concerns, and teens don’t have access to the embodied feeling of confidence they need in order to launch.

photo credit Shutterstock seabreezesky

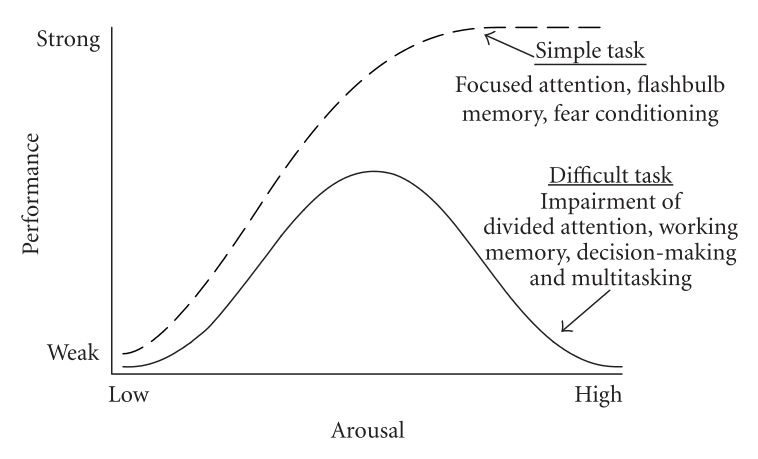

What’s more, these dynamics create chronic stress that burden the nervous system and teens’ development.

“The cellular experience of young people,” Frost said, “is, ‘I’m not safe, this is not safe, and I don’t know what to do about it.’”

A 2022 Stanford University study bears this out: Neuroimaging of brains of 163 young teens before and during the pandemic showed accelerated brain aging due to the pandemic. Areas affected include memory formation, emotion management, and executive function. The changes are similar to those resulting from chronic adversity like violence, neglect, or severe family dysfunction.

Parents’ ability to help regulate kids’ stress decreases at adolescence, creating more vulnerability.

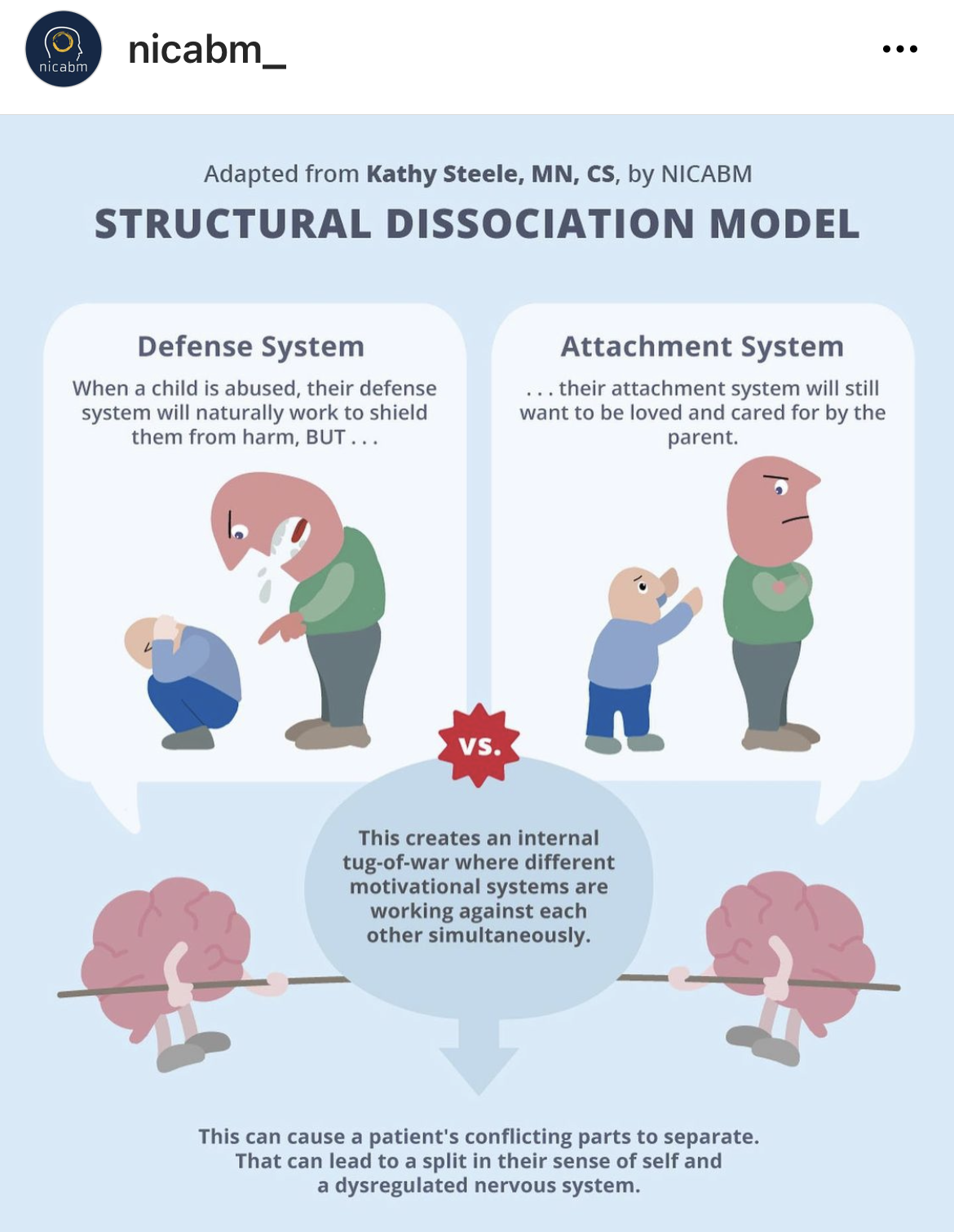

It’s a feature of development that children’s bodies are keenly attuned to signals of stress in their environment, as though they’re “emotional Geiger counters.” Beginning in-utero, signals of stress cross the placenta, causing epigenetic changes that direct a cascade of hormonal, endocrine, and neurological reactions that comprise the body’s hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) system, also known as the stress regulation system.

I spoke with developmental scientist Megan Gunnar at the Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota, who’s been studying the impact of stress on children—and how the body regulates it—for 45 years. “The stress system is very plastic [modifiable] for the first 18-24 months, and then it’s set for awhile,” she explains. “Then puberty helps to reopen it, and adolescence becomes another period of heightened plasticity—for good or for ill.”

About a year before signs of puberty are visible, the sex steroids begin to remodel the brain in preparation for adulthood. An over-blooming of synaptic connections between neurons allows for creative potential, and synaptic pruning eliminates unused connections. As a result, the influences in teens’ lives at that time carry inordinate importance. Teens also become highly sensitive to others, especially their peers. Their reward circuitry is remodeled, boosting their desire to explore their world—and outpacing their “braking system” which takes longer to develop and will make them more cautious, especially in the presence of peers. Some evidence shows that part of the plasticity taking place may involve some alterations to the stress regulation system.

“Adolescents are interested in new experiences, novelty-seeking, especially with their peers,” Gunnar says. “In normal circumstances it’s a wonderful, fabulous time of emotional development,” Gunnar said. But there’s also a feature of the plasticity that makes them more vulnerable. “In adolescence, the parents get ‘booted out’ of their hypothalamus.”

What does that mean? “In childhood,” she explained, “there’s a very powerful capacity of parents, especially in secure relationships, to buffer the child’s reactivity of the HPA axis. The child produces less cortisol (stress hormone) when they’re in the presence of their secure caregivers. But we find in our research that that goes away about the midpoint in puberty. At that time, the parent’s presence no longer automatically dampens the body’s stress response, and teens begin to regulate more on their own—at least in individualistic cultures. (This effect hasn’t been studied in other cultures.) Gunnar’s research is congruent with other research that shows, for example, that, unlike in earlier childhood, teens’ brains are more activated by unfamiliar voices than by their mothers’ voice, consistent with the biological drive to focus beyond the family.

Along with individuation and a greater peer orientation, the downgrade of parental stress regulation may be part of an evolutionary design that nudges young people away from the nest and drives them to form new communities. “Later, when they form an attachment to an adult romantic partner, that partner is ‘let into’ the nervous system,” Gunnar says, “and they will be able to help buffer stress. But in the meanwhile, adolescents are vulnerable.”

Still, Gunnar says, parents can continue to be a regulatory source, helping their teens figure out how to regulate themselves in other ways. “We see in our research that when parents help with emotion coaching, teens are better able to regulate their cortisol response than kids whose parents don’t.”

photo credit E. Frost

Teens are extra sensitive to social evaluation.

Is the teen brain biologically disposed to increased stress? “There is some evidence that there may be a heightened level of cortisol production, overall, in adolescence, but we’re not exactly clear on the mechanisms of that yet,” Gunnar told me. “But work in the Netherlands has shown that there is a heightened level of cortisol production in particular to social evaluative stressors. Adolescents are freaked out by social evaluation, and girls become more sensitive to it before boys.”

In the lockdown, virtual access to others was vital; kids connected with friends and supportive communities across the internet, including on social media and gaming platforms. But some of the interactions may have harmed some of them. In May, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a bracing advisory about the risks of social media to young people’s mental health. It cautioned parents to set limits around social media use, and urged greater regulation and oversight of social media technology companies. One provocative—but nonscientific—global survey suggests that the later a child accesses a smart phone, the better their mental health as adults, especially their self-confidence and social life. Another study shows that lower media use increases teens’ prosocial behavior and self-regulation. Some research blames social media for the mental health crisis, while other research documents individual variation—i.e., some kids feel better using it, and some feel worse.

Regardless, there’s a growing skepticism about smart-phone access and social media use. Therapist Glucoft Wong said she’s seeing more families grappling with recalibrating screen time in their households.

WHAT HELPS?

For parents:

Some kids are fine. The impact of the pandemic was not universally adverse. At scale, the mental health crisis—and shortage of professional help—is alarming. Still, depending on the measure used, statistically one quarter, one third, or half of kids may be alright. Some kids even benefitted. Shy and socially anxious teens, and teens who were experiencing low-grade trauma at school, were relieved by the break. Extra care needs to be taken to reintegrate and support them.

Remember the basics. Sleep, nutrition, exercise and friendships are foundational to all other functioning. One Stanford neuroscientist emphasizes sleep and deep rest above all for wellbeing, and teens are notoriously short on it. Studies show more sleep for teens improves many measures of wellbeing and achievement. Challengesuccess.org offers simple tools to help make conscious choices about time use around the clock.

Focus on psychological wellbeing and emotional skills. All the professionals I spoke with for this article agreed that support for healthy psychological skills is as important as—and perhaps more important than—academic skills. Focus on relationships and emotional health, they advise. This guidance echoes 75 years of research on resilience. Lisa Damour’s book, The Emotional Lives of Teenagers is an excellent place to learn more about how to do that.

Frost and François recommend sharing with teens what you’re learning about wellbeing. Leave materials out for them to read, finish the podcast you’re listening to while you get in the car together, etc. Casual and adjacent sharing helps support teens in a way that’s not didactic or face-to-face.

Make yourself prepared and available to have conversations about things that really matter, about topics that are relevant to your teen. “Teens are meaning-making machines,” Frost quips. “They care about how the world works and their place in it and they want to have conversations about important things.”

Have relationships, don’t just worry about them. “Being in the relationship is more important than the status check-ins of ‘How are you doing?’” Frost and François say. Have supportive family routines, a monthly café date, and be in the world together. “You’re planting seeds for their future and for the future of your relationship. It’s not one big thing, really, it’s how all the small actions day-to-day add up. Even if they balk at your suggestion, it’s worth persisting,” Frost says.

Gunnar concurs: “If I were the parent of a teenager right now, I would be working hard to have that child and the whole family have time when we’re just being a family and not in the media, on screens. Dinnertime, playing games, quieter, simpler things that provide that sense of grounding. And I would do a lot of listening and less talking.”

Clarify emotion language. Frost and François observe that since mental-health language has become more prevalent in our culture, more teens are using terms like “anxiety,” “panic attack,” or “dissociation.” It can be startling at first. Sometimes teens “front” with hyperbolic language; they’re trying it on, but it doesn’t always serve them. Have a growth mindset and see it as an opening for more learning, more talking. Ask gentle questions like, “What do you mean by that?” Tone is everything, says Frost.

In The Emotional Life of Teenagers, Damour reminds us that teens have big emotions in the best of times, and we can often help them understand and manage their feelings. It is when emotions become unmanageable or overwhelming that some professional help may be advised.

Help teens connect to something bigger than themselves. “Young people have a deep longing to feel connected to something bigger than themselves,” François said. “This includes nature, civic engagement, social justice, and volunteering. Getting to be part of a meaningful experience is so key.” Frost adds, “The impact on this generation of being the ‘turning point’ in the climate crisis is underestimated. Their relationship to nature is huge on many levels. And there’s a positive impact of spending time there, experiencing the mystery, the universe, and forces much greater than themselves.”

Reclaim exploration as a part of adolescence. In the 1960s, adolescence was seen as a period of exploration necessary to achieve a healthy identity. We seem to have lost that as we pressure teens to foreclose into decisions, identities, and careers, and as we reduce teens’ free time to be bored and mess around which is critical to developing their unique talents. “Allow kids to not know who they are and still feel valid,” Frost and François advise. Teens interpret even well-intentioned queries as pressure to have answers, and they feel they’re disappointing parents by not knowing.

Take care of yourselves. Teens can be encouraged to be kind and considerate, but they should not be their parents’ emotional caregivers. “Find your communities, find your regulation, your check points,” Frost advises parents, “so you don’t put so much on the teen to reassure you or to give you answers. Teens need to be free of their low-level anxiety about how you’re really doing.”

Connecting with other parents can also help set norms among peer groups, e.g., social media use.

Remember that you’re modeling self-care as well as becoming a better partner inside the relationship for your child to experience.

Resume collaboration with teachers. The three-way relationship among kids, parents, and teachers that has long been proven to support students broke down during the pandemic, Glucoft Wong observes. Parents, kids, and teachers missed out on the benefits of collaborative relationships and friendships and the seamless sharing of information that happens when campuses are open and people interact in person. Reach out to teachers—and other parents—to resume that communication and learn how to best support your students.

Set social media guidelines. A young teen’s brain is very different from that of an older adolescent. In The Emotional Lives of Teenagers, Damour recommends keeping phones out of bedrooms at night and putting age-appropriate brakes on tech access, for example, starting with a phone that can send and receive texts but not access social media. Common Sense Media also has helpful guidelines. But make this a partnership; one study found that excessive restrictions in the absence of communication made teens more secretive and more relationally aggressive.

For educators:

Set later start times and minimize homework. A later school start time for teens is linked to better mental health, and many teens are pressured for time due to too much homework (which isn’t linked positive outcomes).

Acknowledge emotions wisely. Most educators know the importance of a social and emotional education; the challenge is making time for it and embedding it in the school ecology. When emotions are normalized and the school community becomes more skillful, relationships will be deepened and people more skillfully authentic. For ten years now, meta-analyses[DD1] have consistently demonstrated the widespread positive impact of social and emotional learning on adults and students alike.

Create the culture you want. Create social norms for the culture and climate to encourage desired behaviors that become the norm. There are numerous surveys available to schools that let students give feedback about their school culture and assess school climate. Students can also contribute: Research on InspirEd, student-led social and emotional initiatives, showed improvements in school climate, school pride, student relationships and emotional safety.

Provide resources to students. Normalize conversations about mental health and psychological services. Learn what resources are available for your students and communicate those to them. Students need to know who to talk to, how to disclose, and find care in hard moments, like following a sexual assault, when a friend is in trouble, or when they’re invited to participate in harmful behaviors.

Facilitate safe, supportive student relationships across ages. Mentors come in all ages and locations.

Convey hope and inspiration. Students need more than information about problems; they need models and stories that give them hope about their future and their ability to navigate and shape it, without feeling overwhelmed by their responsibility for it. “Teens need honesty, but hopeful honesty,” Frost and François add. “They need to be held in a process of making meaning of what they’re experiencing. Otherwise, where will they get the perspective to face inevitable adversity?”

Model wellbeing. Model how to be an adult and how to achieve the future you want.

* * * * *

Unfortunately, all of the above advice is given in a particularly challenging context. Currently on overall measures of child well-being, the U.S. ranks 36th among 38 nations with comparable high-income economies.

“The nation is getting riled up about the wrong things,” Gunnar says. “We need to be very riled up about how to keep the world a safe place, about critical things like the climate and gun violence. That’s not for the kids to do. It’s for the adults to do.”

In the meanwhile, we can still all have a role in making things better for teens. Growing up in a stressful and unpredictable world will be part of this generation’s story, but in the safety of our patient gaze, warm regard, and reliable support, they may even develop hidden talents—gifts and abilities that we cannot imagine and that only emerge in difficult circumstances. As the author and artist Chanel Miller writes in Know My Name, “You have to hold out to see how your life unfolds, because it is most likely beyond what you can imagine. It is not a question of if you will survive this, but what beautiful things await you when you do….Wait for the good to come.”

photo credit E. Frost

[1] a group convened by the federal government to solve complex national problems and inform public policy