[This post is about the practice of hitting children to modify their behavior, usually referred to as “spanking.” I choose not to use that term here, in part because I feel it minimizes the seriousness of bodily violence against children, and also because the term has been co-opted to refer to a type of consensual sexual play. Instead, I use other terms like “hitting,” “physical punishment,” and “corporal punishment.” Also content notice: There are references to violence and slavery in this post.]

* * * * *

Almost every caregiver has experienced that emergency that makes them want to impulsively discipline their child. For example, your child chases a ball into the street, directly into traffic, unaware of the oncoming truck. You bolt after them, grab them by the arm, and rush both of you to the sidewalk. You’ve just saved your child from getting injured, or worse. You’re terrified and possibly angry, too. For some adults, this intense activation leads them to strike a child.

“Now, why would you hit them?” Elizabeth Gershoff said to me when we discussed the effects of physical force on children. Gershoff is a professor of Human Development and Families Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. For the past 20 years, along with collaborators at other universities, she has been a leading researcher documenting the harmful effects of hitting children for “discipline.”

“I agree we need to get the child out of the street,” she continued. “But the child is already scared to death. They see your fear on your face and hear it in your voice. You’re already communicating the seriousness of the behavior by your emotional expression, your words, and your tone. Those are the tools you already have to express that they cannot run into the street, that they could get badly hurt, that you’re scared, and that if they can’t keep their feet on the sidewalk, then they’ll have to go inside. There are many ways you can deal with the situation that do not require hitting them.”

“If you have to hit somebody, you have lost control,” she said.

Why do adults still hit children?

Hitting a child is a failure of the adult in many ways, Gershoff told me. Sometimes adults misunderstand a child’s behavior and ascribe the wrong intention to it. They think the child was purposely trying to make them mad, get back at them for something, show they don’t care, or even take advantage of them. But most often, what an adult calls “misbehavior” is actually just a mistake on the part of the child, Gershoff said. For example, a preschooler may not know that it’s not okay to write on a wall. To them, that big, white expanse looks like a large canvas or the easel they use at school, and they were simply inspired to color it. It can be helpful for adults to learn more about what children are capable of at different ages and channel a child’s inspiration in appropriate directions. (See some resources below.)

Photo Credit: Mauro Fermariello Science Source Images

What many people won’t admit is that hitting a child can provide an emotional release and a fleeting sense of power for the grown-up. An adult may feel frustrated that they’ve lost control of the child, but when they strike the child, the child stops what they’re doing and usually starts crying. The adult feels vindicated by getting the child’s attention, and their pent-up frustration or anger is released. They believe “it worked,” and the strategy becomes reinforced. Many parental feelings are masked by anger—fear, alarm, loss, grief, shock, shame, etc.—and lashing out can momentarily transfer the uncomfortable energy onto the child—a much less powerful target.

Sometimes physical punishment results from an adult’s failure to supervise and plan responsibly—and maybe the feelings of shame and regret that come up when things go wrong. “Our job is to make a safe environment for children,” said Gershoff. “Why was the child near the street to begin with? Why is the pot on a stove in a position where the child can grab the handle? Why is the electrical socket uncovered? We adults are responsible for making a safe environment for children.” Of course, not every misstep can be anticipated; no parent can make the world 100% safe for their child. When accidents do happen, then, it’s the responsibility of the adult to respond in a way that doesn’t involve physical or emotional harm.

Most people who use physical force were on the receiving end of it when they were children. Studies show that children who are physically punished are more likely to perpetuate the practice as adults, believing that it’s not only normal but necessary for raising children properly. Even the small percentage of pediatricians who still support this kind of hitting—in direct opposition to the official position of the American Academy of Pediatrics—tend to be the ones who were hit as children.

“When a child hits a child, we call it aggression.

When a child hits an adult, we call it hostility.

When an adult hits an adult, we call it assault.

When an adult hits a child, we call it discipline.”

The use of physical force against children has deep roots. Throughout history, children were objectified as sub-human, the property of adults to do with as they pleased. Maltreatment was the norm, and children were “civilized” by routine beatings and worse. In the U.S., it wasn’t until 1974 that child abuse was made illegal. Even then, it was restricted to actions (or failures to act) that caused “serious harm” or death to a child; physical force that did not cause a visible injury, and was intended to “modify behavior,” remained legal. The distinction, though, often falls to the eye of the beholder—a judge or other representative of the state.

Some communities are more apt to rely on physical punishment. Conservative Christians historically believed that children were inherently “depraved” and “filled with the devil,” requiring harsh treatment to become proper adults. Today’s Christian leadership is divided on the issue. James Dobson, therapist and founder of the Christian group, Focus on the Family, advocates the physical discipline of children as long as the adult is “calm” and hugs the child afterward. But two religious denominations, the United Methodist Church, and the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, passed resolutions encouraging parents to use discipline that does not involve corporal punishment.

A 2015 Pew Research Center survey showed that in the U.S., Black families use physical methods to punish their children twice as often as White or Latinx families. “Black parents have legitimate fears about the safety of their children,” writes Stacey Patton, professor at Howard University and author of Spare the Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America. “And the overwhelming majority believe physical punishment is necessary to keep Black children out of the streets, out of prison, or out of police officers’ sight…a belief [that], however heartfelt, is wrong.” She asserts that physical punishment is not a Black cultural tradition; it’s racial trauma.

Charles Blow, New York Times columnist and author of Fire Shut Up in My Bones, concurs. He acknowledges that some people believe that it is better to be punished at home by someone who loves you than someone outside the home who doesn’t. But that is a “false binary between the streets and the strap,” he writes. “Love doesn’t look like that.”

Stacey Patton considers physical punishment through a historical lens: “We cannot have discussions about corporal punishment in Black communities without talking about history,” she writes. Many Black Americans are descendants of enslaved people who were abducted from West Africa. According to historians and anthropologists, there is no evidence that parents in West African societies used physical force on their children. In fact, they believed that children were gods or reincarnated ancestors, arriving from the afterlife with spiritual powers for the good of the community. Hitting a child could make their soul leave their body. But the slave trade increasingly stole younger and younger people, and by the time abolition was imminent, the average age of captives was between nine and twelve. It was impossible for young people to carry child-rearing traditions from their homeland, and once they were in America, adults were under tremendous pressure to make their children docile and compliant in front of white people in order to survive. Today, a number of Black parenting experts advocate for families to break intergenerational cycles of trauma and adopt constructive ways to guide children without physical punishment.

Why do people who were hit as children often become hitters themselves?

A common psychological defense our minds employ is to act out the hurt we’ve experienced at the hands of others by perpetrating it on other people later, even with those we love. This happens when haven’t become aware of our painful feelings or fully examined them.

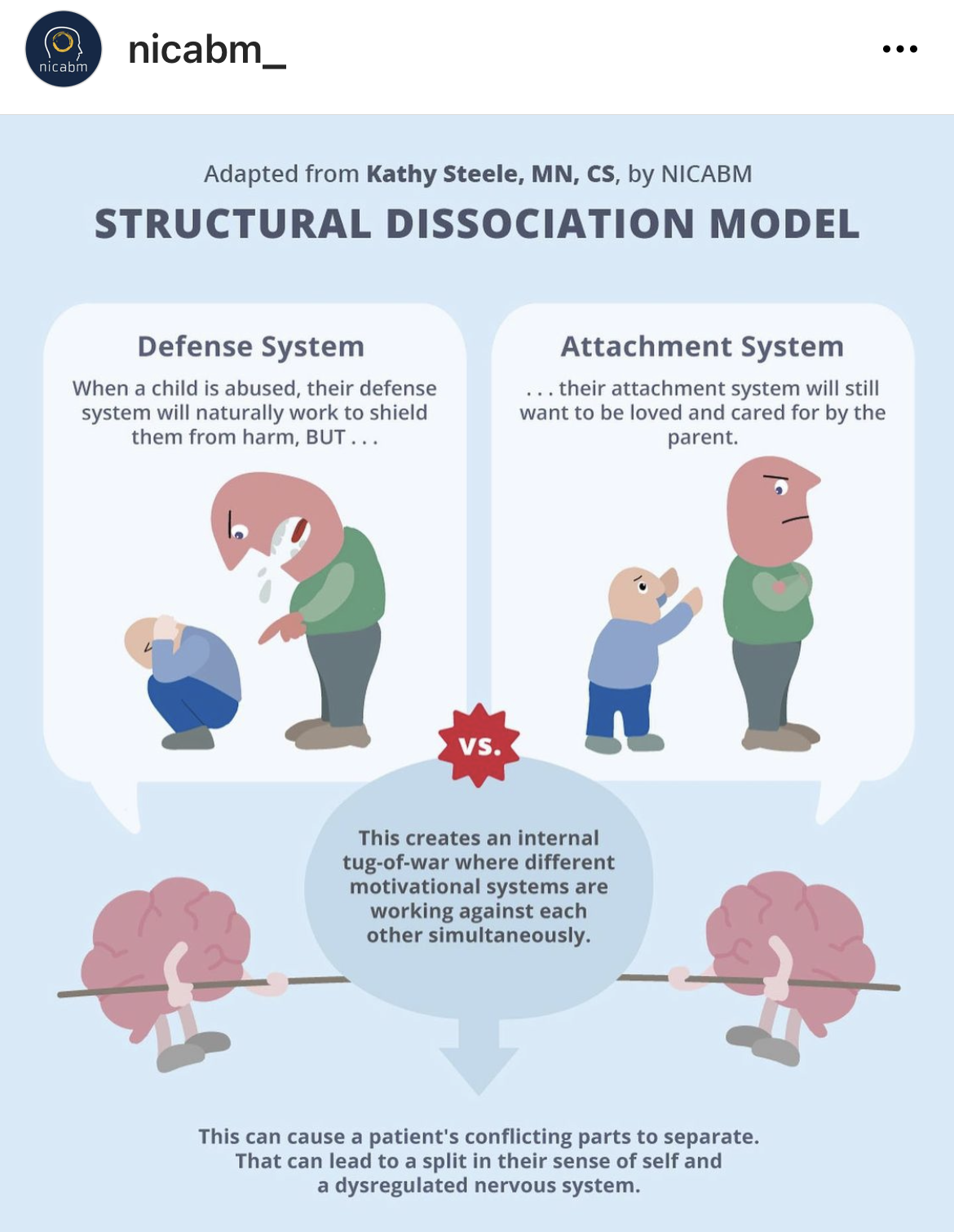

Source: Instagram post from the National Institute for the Clinical Application of Behavioral Medicine

Trauma experts explain why this happens. Children depend on the adults around them for survival. This dependency takes the form of attachment, something I wrote about in a previous post. So when children experience pain from the person who’s supposed to keep them safe, it’s one of the worst kinds of harm they can experience. Their nervous system, designed to keep them safe, begins to get sculpted around the constant threat, creating brain circuitries that are vigilant, reactive, and dysregulated. At the same time, their attachment system needs to keep them in the relationship, so it devises all kinds of excuses: “It’s not that bad;” “I deserved it;” “It made me a better person,” etc. In other words, children dissociate from their feelings of pain and fear.

Kier Gaines, a therapist, social media influencer, and father of two, describes the dynamic in an Instagram video that went viral. “The men that were a generation before us, got raised by the men that were a generation before them, and those men didn’t really know warm love….Before you take on a family,” he says, “go see somebody about your past. Go see somebody about the trauma you’ve endured throughout your life, and start healing.”

Hitting children, even for “discipline,” is a form of trauma.

Some adults cling to the excuse that a single swat on the bottom, or one slap on the head, can’t be that bad, and is necessary to “teach them a lesson.”

“Is there any kind of hitting that works to change behavior?” I asked Gershoff.

“There’s no situation that I can imagine where physical punishment is useful or necessary,” replied Gershoff. “It doesn’t teach children to behave well. It’s not effective for reducing aggression, or teaching self-control or prosocial behavior, or any of the things parents hope to teach children. It’s not effective in either the short- or the long-term.”

Physical punishment is one of the most intensely studied aspects of parenting. Hundreds of studies over five decades have concluded that it’s harmful to children in just about every measurable way. Children’s behavior, emotions, intellectual functioning, and physical health all suffer. Gershoff’s most recent 2016 meta-analysis with Andrew Grogan-Kaylor, professor of social work at the University of Michigan, analyzed 75 studies involving 161,000 children. Three important conclusions were drawn:

First, consistent with earlier research, the analysis found no evidence that physical punishment changed the original, unwanted behavior.

Second, there were 13 significant harmful effects of the practice:

Poorer moral reasoning

Increased childhood aggression

Increased antisocial behavior

Increased externalizing behavior problems (disruptive or harmful behavior directed at other people or things)

Increased internalizing behavior problems (symptoms of anxiety or depression)

Child mental health problems

Impaired parent-child relationship

Impaired cognitive ability and impaired academic achievement

Lower self-esteem

More likely to be a victim of physical abuse

Antisocial behavior in adulthood

Mental health problems in adulthood

Alcohol or substance abuse problems in adulthood

Support for physical punishment in adulthood

Third, these outcomes were similar to effects of childhood trauma. A landmark set of studies in the 1990s documented that exposure to certain kinds of childhood experiences—including physical and emotional abuse or neglect, sexual abuse, domestic violence, family mental illness, incarceration, and substance abuse—causes great harm lasting into adulthood. And the more adverse experiences a child has, the greater the impact. The effects include increased risk for serious physical diseases like cancer, diabetes, heart disease and COPD as well as early death, mental illness, suicidality, lower educational and professional attainment, and even reduced income. As a result of these findings, a ten-question screening tool known as the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Checklist is now widely used to identify risk for mental and physical illnesses due to ACEs, in the hope of providing early intervention and treatment.

Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor analyzed a subset of seven studies from their meta-analysis that compared the use of physical punishment to physical abuse and found that the impact was indistinguishable. Both physical punishment and physical abuse led to more antisocial behavior and mental health problems in childhood as well as increased mental health problems in adulthood. In a separate study, Gershoff and colleagues reanalyzed a subset of the original ACEs data and also found that physical punishment was associated with the same mental health problems in adulthood as physical and emotional abuse. In addition, it created an even greater likelihood of suicide attempts and substance abuse than physical and emotional abuse alone created.

Brain imaging studies also show a link between physical punishment and trauma. In a 2021 study, researchers showed 147 12-year-olds pictures of fearful and neutral faces while their brain activity was imaged in a functional MRI (fMRI) machine. Compared to children who were never physically punished, children who were physically punished had greater activity throughout the brain when viewing fearful faces. They also had more activity in regions of the brain related to threat appraisal, emotion regulation, and evaluating the mental state of others. Importantly, the pattern of their brain activity was the same as children who had been physically abused. When children have harmful interpersonal experiences, they become hypervigilant to the emotional expressions of others, because fearful or angry adult faces can be a cue that something bad is likely to follow. This study suggests that children who are physically punished are running the same brain circuitry as children who have been abused.

Data like this shows that the attempt to distinguish between physical punishment and physical abuse is no longer legitimate. What we now know is that inside the child, the response is the same. According to Gershoff, “Research like this may help parents understand that when they’re hitting their children, they’re causing fundamental damage to the child’s brain—not because they’re hitting them in the head. They’re hitting them in other places on their body, and it’s causing a massive stress reaction every time. And it gets worse every time it happens. That stress ramps up and ramps up and causes physical and mental health problems.” As a result, Gershoff and colleagues, and many other scientists, call for physical punishment to be identified and screened for as an additional ACE.

Other countries are far ahead of the U.S.

Worldwide, three out of four (close to 300 million) children two-to-four years of age are punished with violence regularly, including physical punishment or verbal abuse from parents or caregivers. In some countries, children as young as 12 months are regularly hit, according to a 2017 UNICEF study.

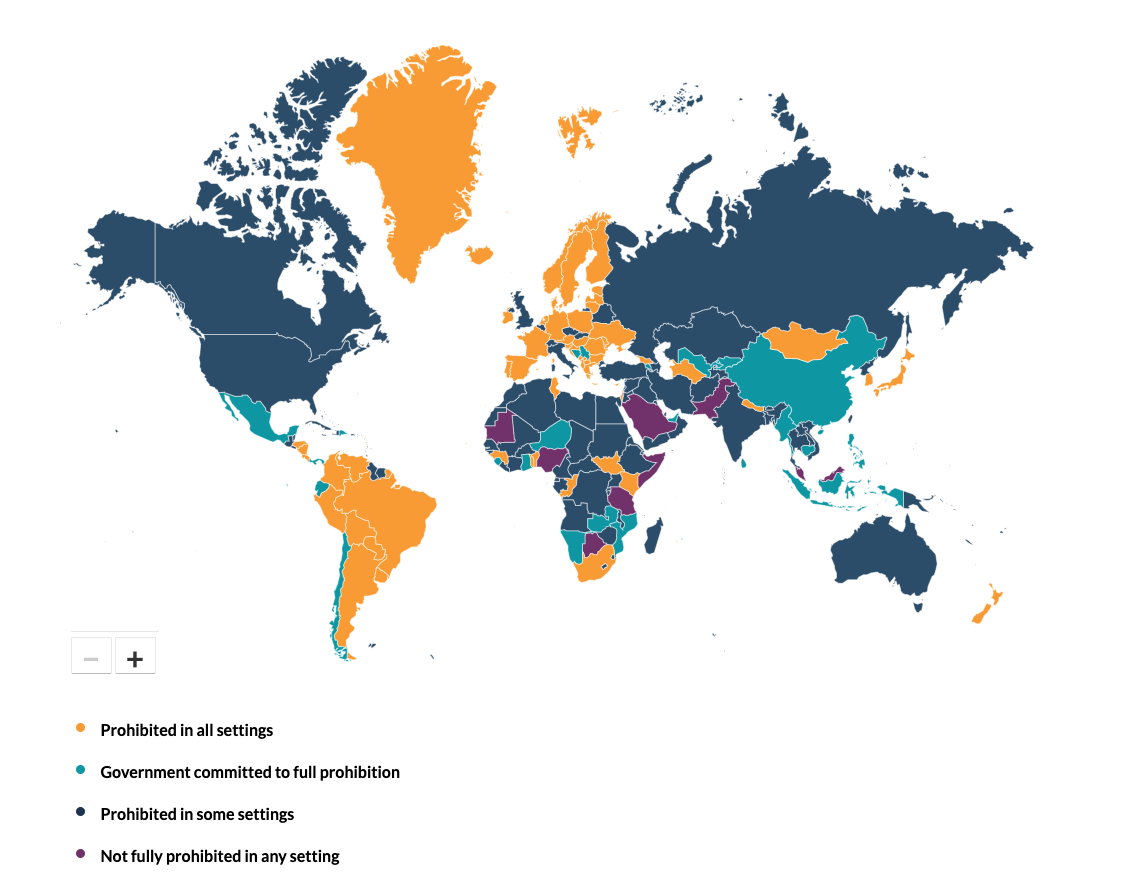

But momentum is growing to outlaw corporal punishment of children in all settings, including home and school. (The term “corporal punishment” is used internationally, and in the U.S. it refers to physical punishment in schools. It’s defined as the intentional use of physical force to cause pain or discomfort, or non-physical force that is cruel or degrading.) Currently, 63 countries have a full prohibition on corporal punishment, inside and outside the home. The map below shows the status of each country. (This link takes you to the interactive map, where you can find more details about each country’s progress.)

From: End Corporal Punishment

In U.S. homes, though, physical punishment remains legal in every state. Even in the case of abuse, some judges will excuse it if it was intended to “discipline” children, under a “parental discipline exemption.”

As for schools, corporal punishment is outlawed in 31 states and the District of Columbia, but it remains lawful in 19 states, in both public and private schools. Gershoff consulted with Congressman Don McEachin and Senator Chris Murphy on a bill to ban corporal punishment in schools, Protecting Our Students in Schools Act. “It didn’t get momentum,” she told me. “I don’t think people realize it’s still happening in schools, but nearly 100,000 kids get paddled with boards each year in school, primarily in states in the South.”

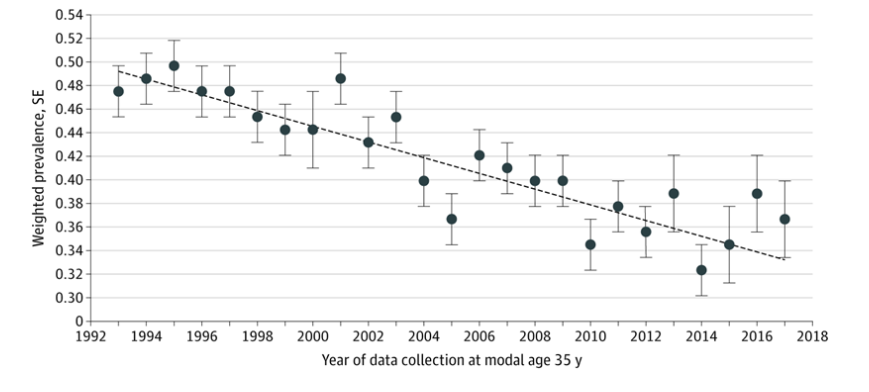

Even without progress at the government level, public opinion and practices are gradually changing. A U.S. study of 35-year-old parents conducted every year from 1993 to 2017 asked the question, “How often do you spank your child(ren)?” The graph below shows the decline in the percentage of parents reporting any spanking at all, from about 50% in 1993, to about 35% in 2017.

Recently, a colleague and I were facilitating a parent meeting at a school, squeezed into child-sized chairs in a circle, when an older woman rushed in, late, and breathless. After she settled into her chair, she shared: “I’m taking care of my two grandchildren while my daughter is in jail,” she said. “I hit my own kids, and I know that’s wrong. But I don’t know what to do instead.” I was moved by her vulnerability and her determination. One of the most important jobs we have as parents and caregivers is to protect our children from our worst selves. I could see her commitment to stopping the intergenerational transmission of violence.

Parenting is hard. We love our children, we nurture their gifts, and we teach self-control and acceptable behavior. There are many positive, gentle, respectful ways of guiding them forward that begin with our own awareness, education, and self-regulation. This is a larger topic for another post, but as a starting point, I’ve listed a few of my favorite resources below.

“It took us until 1994 to ban violence against women,” Gershoff told me in closing. “Now we look back and wonder why anyone ever thought violence against women was okay. I think we’re in the middle of a similar gradual shift regarding hitting children. We’ll eventually get there, but we haven’t quite had the sea change yet. I’m hoping it will come.”

“…There is no ambiguity: ‘All forms of physical or mental violence’ does not leave room for any level of legalized violence against children. Corporal punishment and other cruel or degrading forms of punishment are forms of violence and the State must take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to eliminate them.”

“Parents, other caregivers, and adults interacting with children and adolescents should not use corporal punishment (including hitting and spanking), either in anger or as a punishment for or consequence of misbehavior, nor should they use any disciplinary strategy, including verbal abuse, that causes shame or humiliation.”

“Physical discipline is not effective in achieving parents’ long-term goals of decreasing aggressive and defiant behavior in children or of promoting regulated and socially competent behavior in children….The adverse outcomes associated with physical discipline indicates that any perceived short-term benefits of physical discipline do not outweigh the detriments of this form of discipline….Caregivers [should] use alternative forms of discipline that are associated with more positive outcomes for children”

Additional Resources

Alternatives to hitting:

A secure attachment and an authoritative parenting style set the foundation for closer relationships and cooperation — see my earlier blog posts for more.

In addition, there are lots of wonderful resources on Instagram and TikTok. Look for people who advocate gentle parenting, positive parenting, or respectful parenting. Here are some of my favorites on Instagram:

@respectfulmom, @mrchazz, @biglittlefeelings, @babiesandbrains, @dr.katetruitt, @the.family.coach, @wildpeaceforparents, @greatergoodmag, @ceciletuckercounselling, @kiergaines, @thedadgang, @the.dad.vibes, @laura._.lovee, @gottmaninstitute, @parentingtranslator, @parenting_pathfinders, @dr.annlouise.lockhart, @dr.siggie, @parentstogether

Books:

No Bad Kids: Toddler Discipline Without Shame by Janet Lansbury

The Whole-Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind

by Daniel Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson

How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk, by Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish

Between Parent and Child, by Haim Ginott

The Secrets of Happy Families: Improve Your Mornings, Rethink Family Dinner, Fight Smarter, Go Out and Play, and Much More, by Bruce Feiler

What to expect of children at different ages:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Developmental Milestones

American Academy of Pediatrics: Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents

On hitting and trauma:

Many good resources are available at the Trauma Research Foundation

The Body Keeps the Score, by Bessel van der Kolk

What Happened to You? By Bruce Perry and Oprah Winfrey

For Your Own Good, by Alice Miller

Spare the Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America, by Stacey Patton