Massive unemployment. Loss of life. Disrupted education. And an economy in free-fall. These are the ingredients for the kinds of tectonic social shifts that alter the arcs of human lives. And parents, as always, are at the fulcrum of the pressures, protecting their families while trying to hold together a semblance of normalcy for their children.

Photo Mangolis Lagoutaris, Getty Images

For 100 years, developmental scientists have studied how families and children respond to disasters, manmade and natural. From the Great Depression to Hurricane Katrina, from 9/11 to wars and historic migrations, we’ve learned a few things. Studies of resilience have shown us that certain conditions enable children to adapt well amidst adversity, and other conditions lead to unfavorable outcomes.

The most critical element, according to the research, is the presence of at least one stable, caring adult, someone who provides a secure psychological container and a scaffold for growth—and I’ll explain that more fully below. But there are other levers at play, too.

In times of societal crisis, the following qualities are important to a child’s psychological resilience. I share these with you in the hope that whatever your situation in caring for children during the pandemic, you can focus on what really matters to your family’s long-term psychological well-being and let go of the more minor concerns.

Dosage

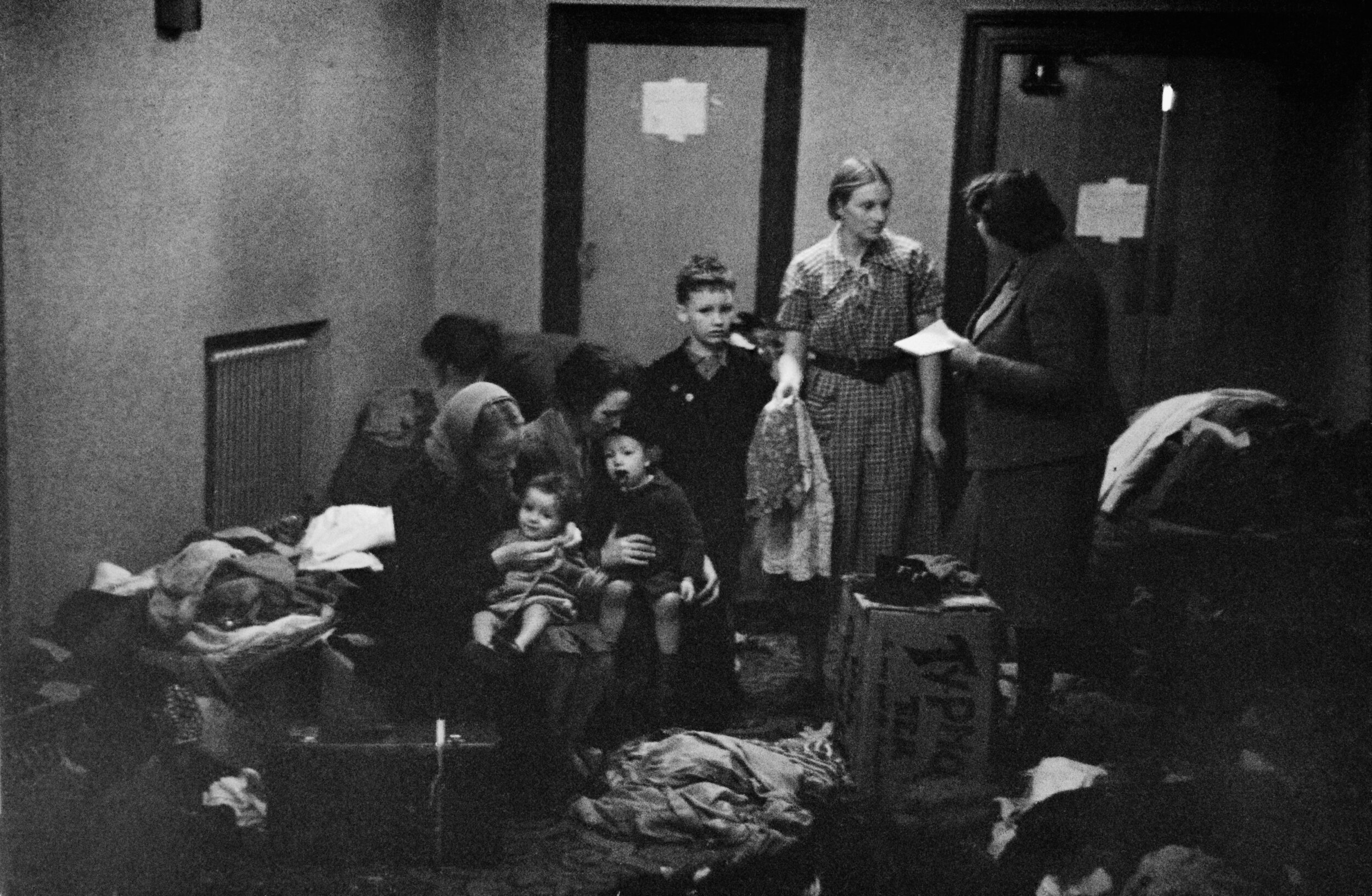

photo credit: Fred Ramage, Getty Images

Research on children’s resilience began with developmental psychologist Emmy Werner, who was a child during the horrors of World War II in Europe. Many of the 39 million civilians who died because of the war were children, and 20 million children were orphaned. Werner managed to survive with her cousins by “foraging in the ruins of bombed-out houses and in abandoned beet, potato, and turnip fields” when all of the adult males in her extended family perished on the battlefield or in prisoner camps.[1]

In order to explore how children survived, she studied the letters, diaries, and journals of 200 child eyewitnesses on all sides of the war across 12 countries. In addition, Werner conducted in-depth interviews with 12 adult survivors when they were in their 50s and 60s.

In her book, Through the Eyes of Children, Werner writes that many of the children who survived became adults with “an extraordinary affirmation of life.” However, children were affected differently depending on a number of variables. The most important was their level of direct exposure to violence, bombing, and combat. For example, in a study of 1200 British school children targeted in air raids, 18 percent had symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), e.g., intrusive fears; nightmares; sleep disturbances; and heightened reactivity to loud noises, like sirens and explosions. These symptoms were present five years later at a rate comparable to those found in combat veterans of WWII and, later, the Vietnam War. When Werner interviewed her adult subjects more than 50 years later, they still reported frighteningly vivid memories of the sounds of air raid sirens, machine gun fire, and low-flying planes.

(Getty Images: Hulton Deutsch, Fred Ramage, Fox Photos)

Studies of children worldwide in other wars and conflicts, from South Central Asia to Rwanda to Ireland, corroborate that the dose is the poison. In other words, the degree or length of exposure to danger is strongly predictive of later disturbance.

photo Jose Jimenez Getty Images

This was true, too, for children who were alive at the time of the collapse of the Twin Towers in New York City on Sept 11, 2001. Representative studies of children and adolescents following the attacks showed that the greater the degree of direct or indirect exposure, the greater the symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and separation anxiety, and of course children who experienced the loss of a family member suffered most. The proximity of children to the event when tragedy struck mattered. A study of 844 children showed that those who were below Canal Street when the towers collapsed, and witnessed the event or were out in the dust soon after, had more psychiatric and physical health disorders at ages 17-30. Those same children had four times the rates of both disorders co-occurring, compared to a control group of children who were across the bridge in Queens and only saw media coverage of the event.

But media coverage, too, is a kind of chronic exposure, albeit indirect. A study of middle school children who watched repeating loops of television coverage of the Oklahoma City bombings showed that they were more likely to have symptoms of PTSD seven weeks later (even though none of their families were harmed), compared to children who watched less television coverage.

Takeaway: Children with the most direct exposure to the pandemic—e.g., who lose a loved one or whose family is struggling with the disease, food shortages, or other deprivations—may be most at risk for psychological disturbances and should be prioritized for services and resources.

If possible, shield children, especially the youngest, from media exposure so that caregivers stay in control of the messages. Four- to six-year-olds can handle minimal, manageable facts about why their lives have changed. Teenagers can take in more information and are interested in understanding how the world works and their place in it. But even then, caution is warranted. It’s helpful to have a wise adult in the wings to talk about events and emotional responses, and extra care should be taken with sensitive or empathic teens, as they can become overwhelmed and anxious more easily. Staying constructive and action-oriented helps to mitigate the chances of depression and overwhelm.

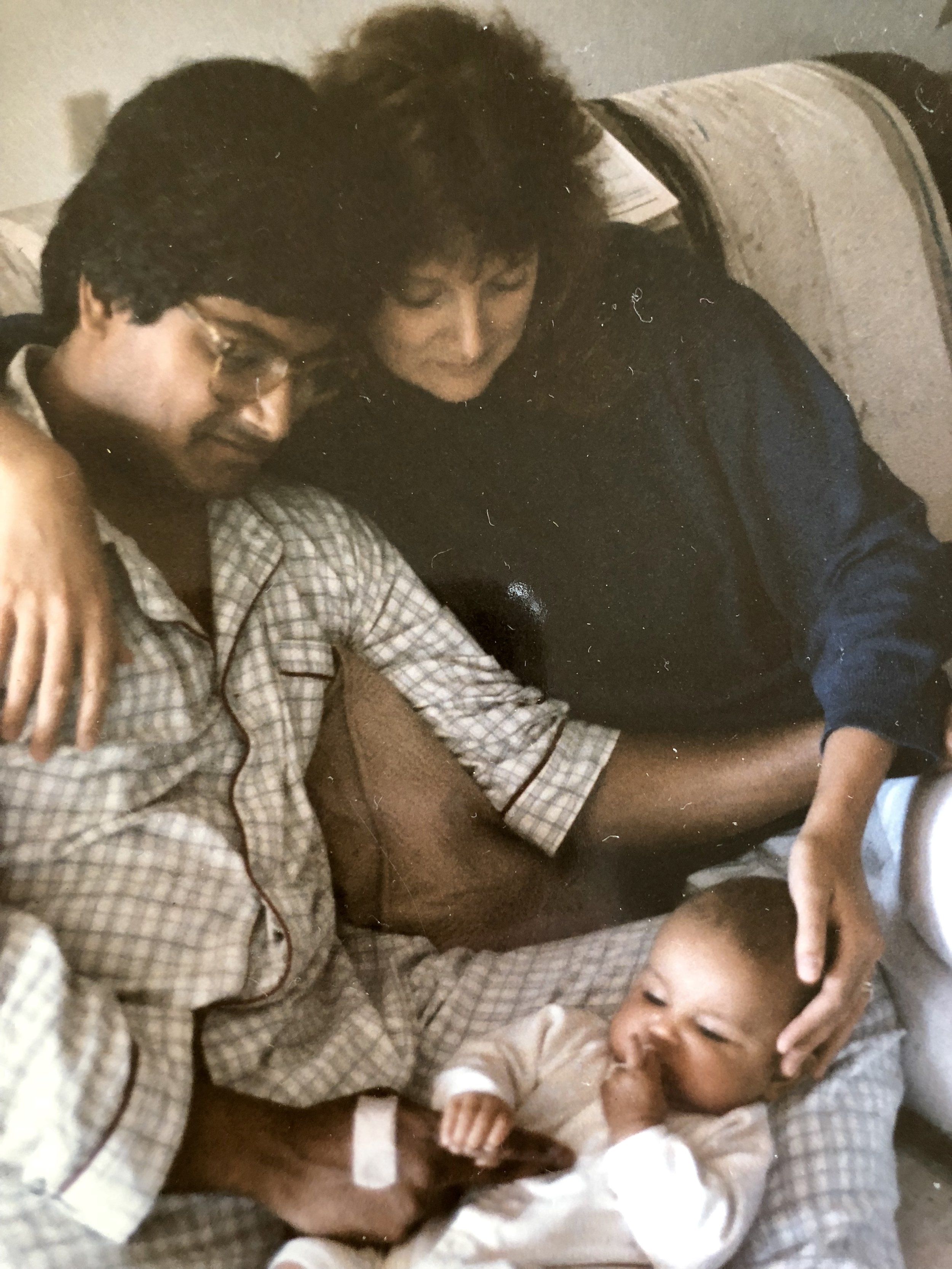

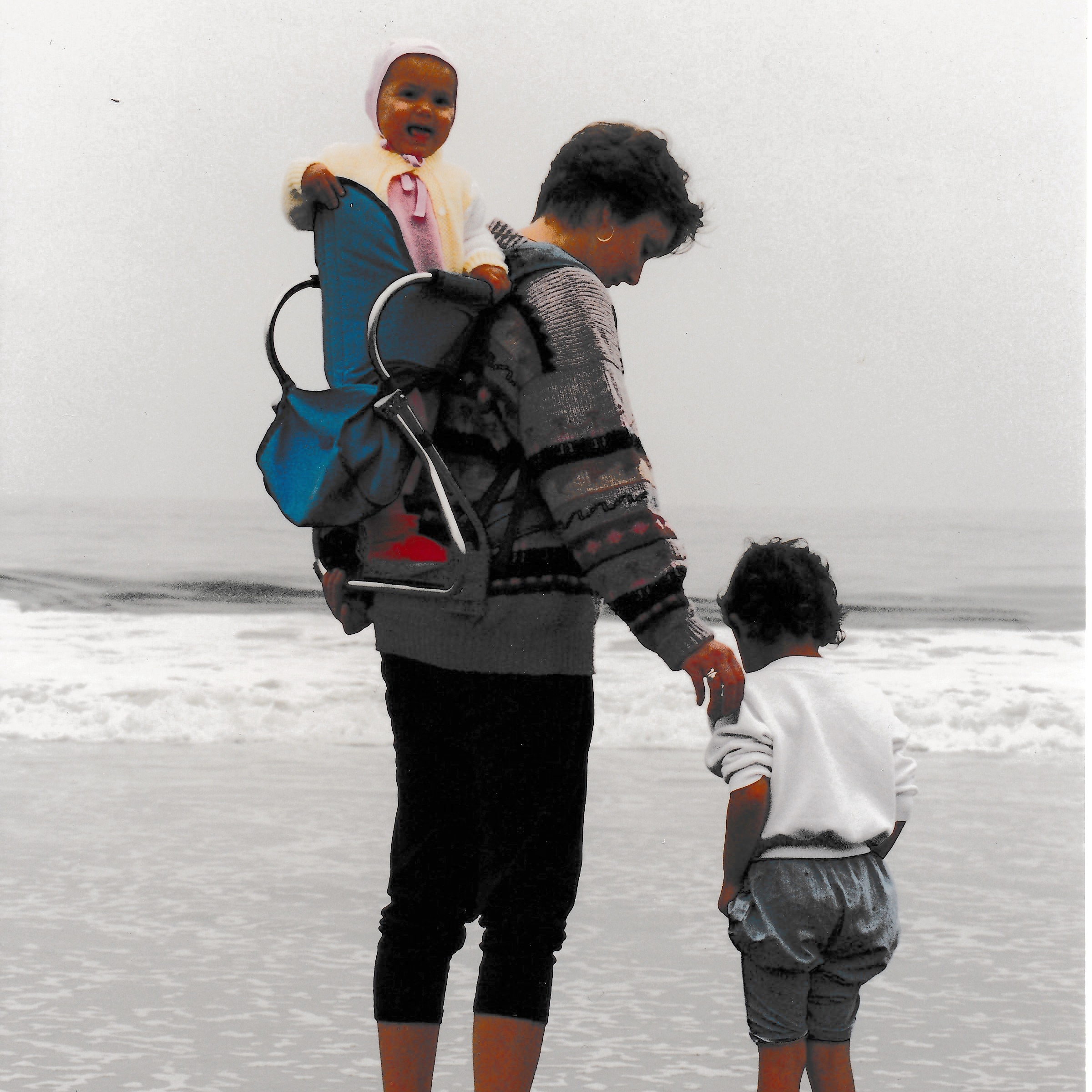

Availability of loving caregivers

When uncertainty or danger strikes, children are “wired” to look to their caregivers to determine how safe they should feel. If their primary adult is calm, a child feels reassured. But if their adult is upset, the child feels unsafe, and their body and brain go into threat mode. And when the threat system is on too long without relief, physical and mental health problems can result.

The first documentation of the protective effect of a caring adult also came from observations of children during WWII. Anna Freud, daughter of Sigmund Freud, founded the Hampstead War Nurseries in England to care for children during the Blitz, the Nazi bombing campaign of the United Kingdom from 1940-41. Freud and her colleague Dorothy Burlingham documented their observations of children in their care in their book War and Children.

Though the children were not exposed to direct combat, they lived through repeated, unpredictable air raids throughout the day and night. Some children saw death up close, some were buried in debris, and many were injured. Freud and Burlingham found that, remarkably, when children were with their family members during these events, they rarely showed “traumatic shock.” They showed “little excitement and no undue disturbance. They slept and ate normally and played with whatever toys they had rescued.” The children seemed to equate their experience with just another childhood “accident,” like falling out of a tree or getting thrown off their bike. That the war “threatened their lives, disturbed their material comfort or cut their food rations” mattered little, according to Freud and Burlingham, as long as the children were with a trusted adult.[2]

But it became “a widely different matter” if a parent was killed or a child was separated from their parents. Children had a much harder time, for example, if they were evacuated for their safety to the countryside. Separation from parents was worse for children than enduring the bombings alongside their family, write Freud and Burlingham. This has been true in every war zone studied, from Rwanda to Bosnia and the West Bank to Syria. Studies show that if children lose the sense of safety anchored by a secure caregiver, the result is often an increase in PTSD, desensitization to violence, anxiety, depression, aggression, and/or antisocial behavior.

However, when the parent is present, their own emotional state matters. Freud and Burlingham write that most of the London population met the air raids with a “quiet manner,” so it was extremely rare to find children who were “shocked.” For example, they describe one Irish mother of eight whose windows were blown out in a bomb blast. When she showed up at the clinic, she said that they were “ever so lucky” because her husband was there and could fix the windows. Another mother brought her daughter in for a “cough and cold” but didn’t think to mention that they’d just escaped a bomb shelter destroyed in a fire. Due to the mother’s “lack of fear and excitement,” Freud and Burlingham write, the child “will not develop air-raid anxiety.” By contrast, they noticed that very anxious mothers had very anxious children. For example, one five year-old boy developed “extreme nervousness and bed wetting” when he had to get up in the night, get dressed, and hold his trembling mother’s hand.[3]

Photo Bert Hardy Getty Images

More recent research confirms that depression or anxiety in the primary caregiver is a significant risk factor for children’s psychological health. Anxious parents can overlook their children’s needs, and depressed parents usually under-respond to their children; either situation can lead to missed emotional cues and mental health problems in children.

Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University

On the other hand, when a supportive adult is present, the child can tolerate much more than if they were alone. Simply the presence of a calm adult can reduce the levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, in a child’s body. In fact, this supported exposure to manageable stress can even be “inoculating,” helping children to be more resilient, whereas complete avoidance of stress undermines the development of resilience.

The supportive adult figure doesn’t have to be a parent. Research shows that any non-parental figure in a caring capacity, including a neighbor, teacher, counselor coach, sibling, or cousin, etc., can be just as effective.

In addition to her study of children in WWII, Emmy Werner also conducted a 40-year longitudinal study on the Hawaiian island of Kauai to investigate the long-term effects of poverty and family dysfunction on children. She found that one of the strongest predictors of a child’s resilience was an emotional bond with an adult outside the immediate family.

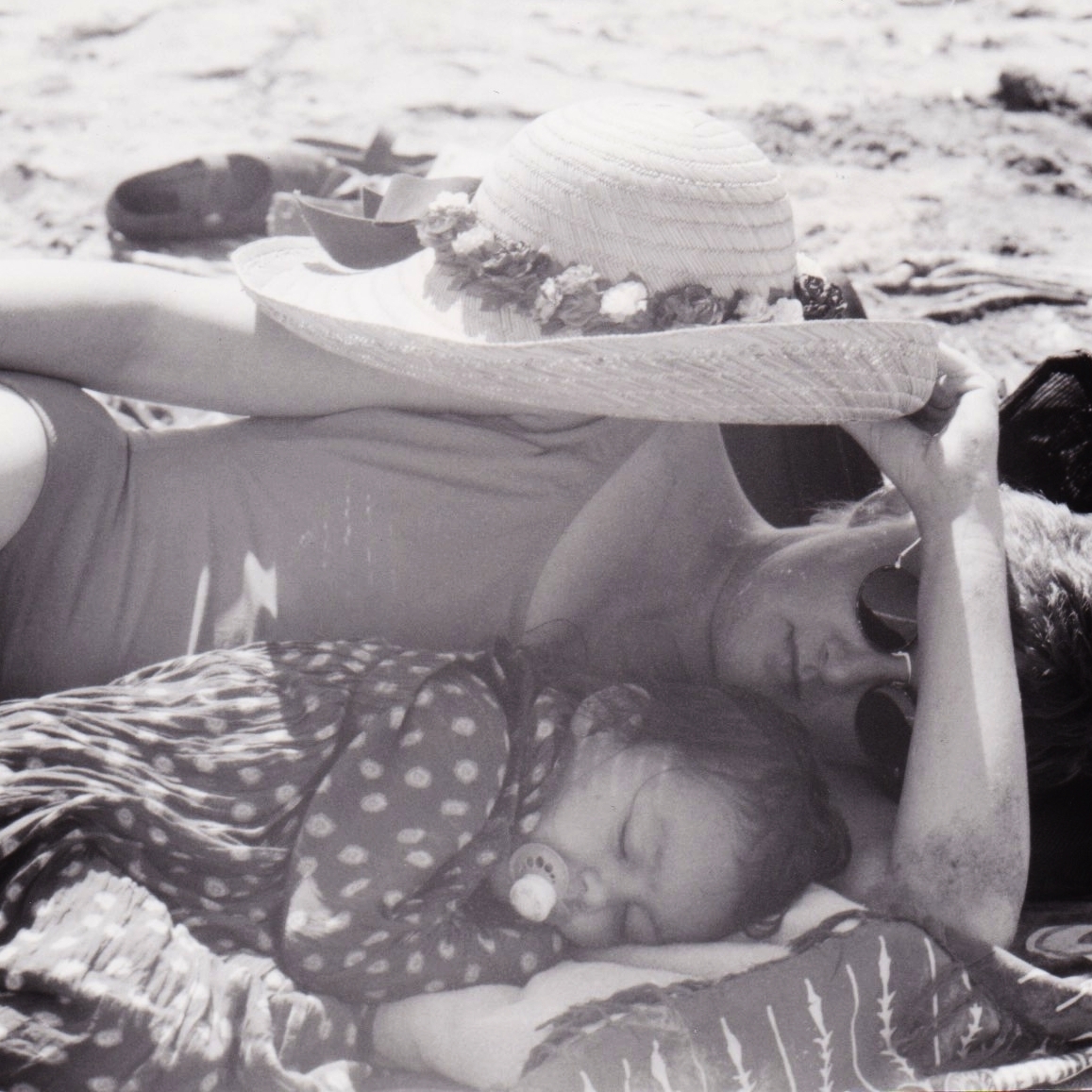

photo Robert Sullivan Getty Images

This correlation was also found in a study of children in New Orleans who survived the flooding and aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Children who fared the best seven years later were the ones who’d had the most supportive connections—family members, teachers, pastors, or shelter workers. By contrast, those who fared worst had lacked any constructive connections, and the ones who floundered marginally had had only one person as a solid anchor.

Werner also studied the records of pioneer families who travelled across deserts, mountains, and rivers in wagon parties. The Donner Party is perhaps the most tragic and well-known story of westward migration. A small band of 87 travelers took an ill-advised shortcut away from the Oregon Trail and onto a lesser known route around Salt Lake. The path eventually ended, and they had to cut through forests and brush to clear their way. The delay caused them to get trapped in the heavy Sierra snowfalls, unable to move for four months. As supplies dwindled, travelers resorted to eating their animal skin rugs and animals, and a few resorted to cannibalizing their deceased companions. Of the 41 children in the party, a third died, mostly infants and toddlers.

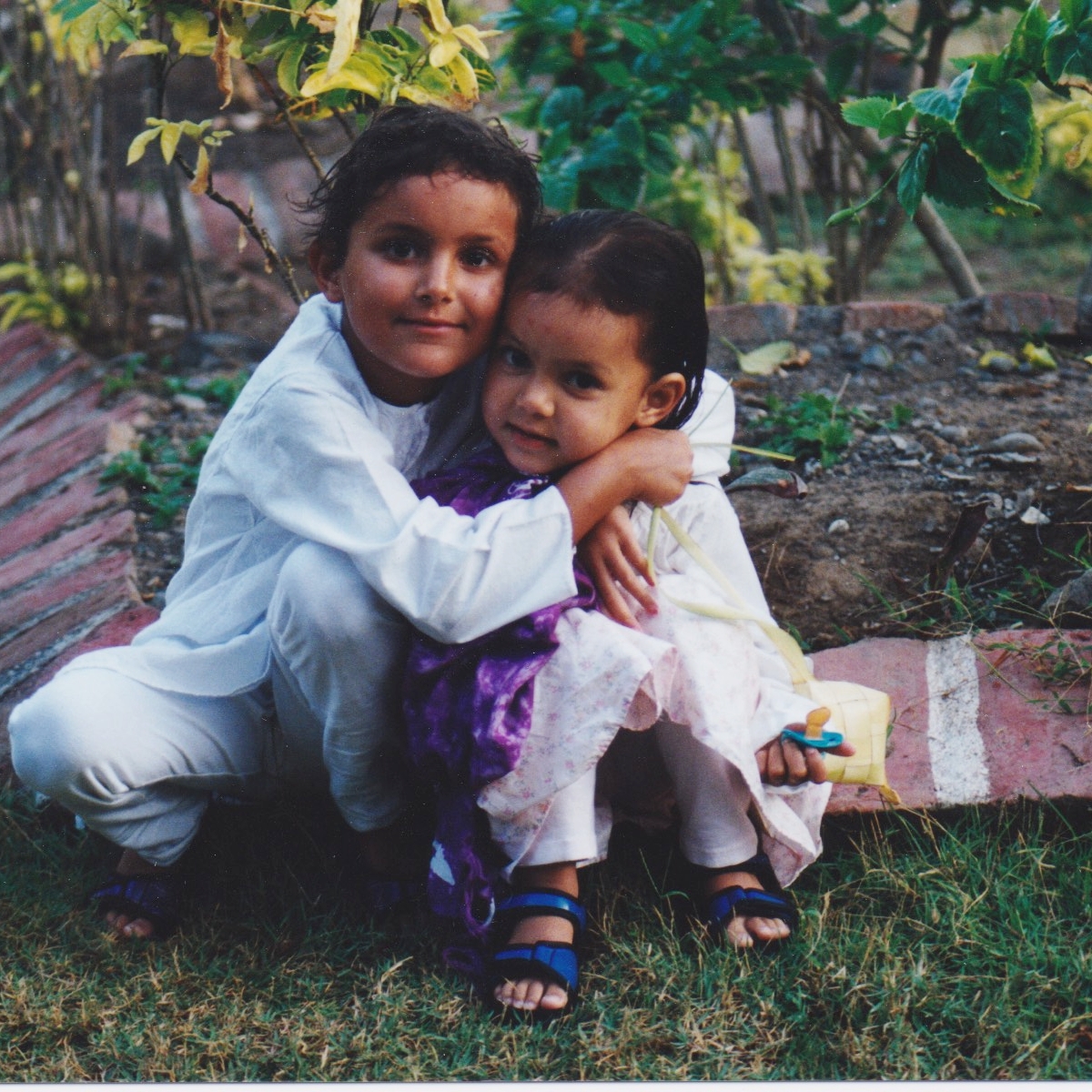

The ones who survived, according to Werner, had the strongest social supports from mothers, aunts, cousins, and a teacher who pooled what resources they had, maintaining whatever shreds of structure and normalcy they could muster. Werner details the particular significance of the sibling bond. Siblings shared food and drinks, nursed the sick and injured, and were confidants and supports to each other when the going got tough. The majority of children who survived went on to lead “long and productive lives,” becoming lawyers, ranchers, writers, prospectors, and heads of large families.[4]

Takeaway: Children are most resilient when they’re embedded in a network of social support: a parent, a caring parent figure, and/or siblings. Accounts like these suggest that the support that works for children doesn’t have to be overly-precious or hyper-conscious. Rather, practical, positive decency offered by ordinary people will suffice.

The message to parents who aren’t able to care for their own children because they’re essential workers—or are sick and quarantined away from their families—is that other committed adults can pinch-hit as caregivers just fine.

For stressed parents at home caring for children 24/7 and trying to work, too: Put on your oxygen mask first. Your self-care is essential. It’s a consuming challenge to bring your best self to this quarantine day after day, but your wellbeing is essential to you and your children. And rest assured, you don’t have to be perfect. Even in the healthiest relationships, parents are only “in-tune” with their children 30% of the time. What matters more is your flexibility to repair, to come back together, and perhaps to reunite at the end of a long day. Apologies, forgiveness, and self-compassion are key. Remember: the biggest lesson your children are learning from you is how to handle themselves in stressful situations.

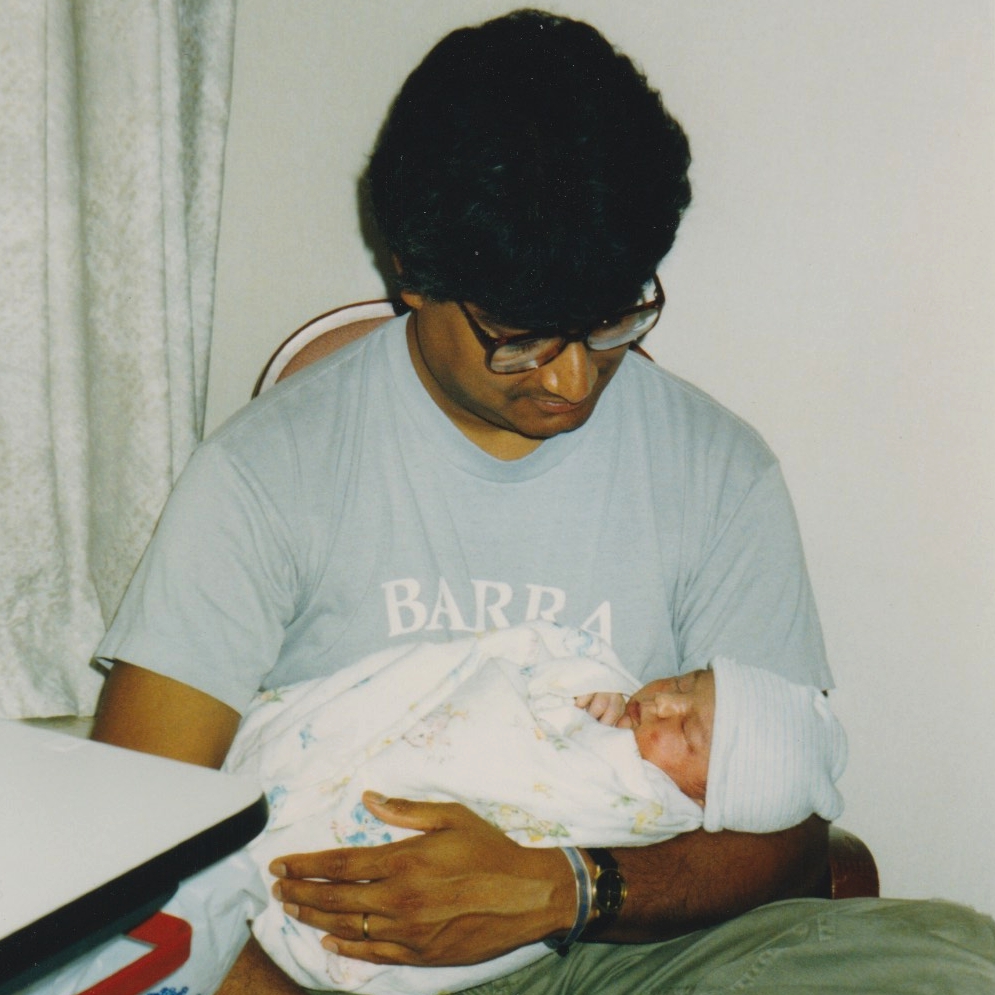

Child characteristics

What about the characteristics of children? Do some kinds of children do better than others?

First, there is no “resiliency gene,” but difference in biological makeup does affect how children register and regulate stress. These foundations are created by genetic and epigenetic transmissions across generations and by childhood experiences, especially during sensitive periods. The physiology of the stress regulation system is established from the prenatal period, through the first three years of life, so the stress experienced during that time is very influential in shaping stress-sensitivity of a child’s system. However, research also shows that in puberty—a period of brain remodeling—a child’s stress physiology can be recalibrated for better or worse, depending on how much stress they’re experiencing.

About one in five children is more biologically “sensitive” to stress than others. Their “fight-or-flight” systems react more quickly, easily, and intensely to mild stressors. They can become more devastated in difficult conditions, even more susceptible to respiratory illnesses. But they bloom more brilliantly in favorable conditions—becoming the world’s artists, poets, inventors, and empaths.

The first wave of resiliency research presumed that children who were more easygoing and sociable (i.e., could enlist other people’s help), and “intelligent” did better. Newer research has refined those generalizations into more specific abilities.

Recent studies have pointed to certain kinds of cognitive and emotional skills related to resilience. Executive control involves the higher-order thought processes in the prefrontal cortex. These include self-management abilities like setting goals, devising a plan to accomplish the goal, problem-solving, flexibility, and monitoring progress along the way. Historical studies show that a family’s survival often depended on the contributions of children, and that the mastery and competence the children developed through these tasks served them well in their adult lives.

Emotion regulation is the process of monitoring feelings and using strategies to minimize unpleasant ones (down-regulation), increase pleasant ones (up-regulation), and maintain desirable ones in order to accomplish a goal. Positive strategies include reframing, acceptance, and finding a purpose. Drawing on children’s unique inner resources, like friendliness, musicality, humor, building, organizing, or creating can help keep their focus constructive. Unhelpful strategies include ruminating, numbing, escapism, venting, blaming, and disengaging; all of these lead to greater anxiety and poorer mental health outcomes in children.

Resiliency studies show that a combination of executive control and emotion regulation leads to the best outcomes and the lowest anxiety in children.

Takeaway: Some children may need a little more attention and support than others because of their age or their sensitivities. Pregnant women, infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and young teens need extra support and stress-buffering. It’s a good time to model, demonstrate, and teach executive control (e.g., through planning and completing projects) and emotional skills. Many professionals have suggested that during this time, traditional school lessons may be less important than social and emotional ones.

Prior vulnerability

Whatever the future effects of the pandemic on children and families, according to Jack Shonkoff, pediatrician and director of the Center for the Developing Child at Harvard, they will not be evenly distributed across families. Vulnerable families who already struggle with difficulties such as poverty, food insecurity, racism, immigration stress, and disabilities will experience more breakdowns like substance abuse, family violence, mental health problems, and later educational and employment challenges.

We’re already seeing news reports of faltering families. Divorce rates spiked in China following the peak of the pandemic, and early reports are signaling a similar trend in the U.S. The United Nations has reported a “horrifying” increase in domestic violence. As of this writing, calls to police and domestic violence hotlines are up 15-20% in New York; they’ve doubled in Lebanon and Malaysia, tripled in China, and increased 75% in Australia. Quarantined victims are trapped at home without access to teachers, counselors, or doctors who could support their emotional and physical safety. Part of the U.S. government relief package provides funding for shelters and hotlines. It seems that disasters that immediately threaten mortality like 9/11 or wars are less likely to spike family disturbance, but those that become chronic stressors like unemployment and the quarantine bring out the worst.

The disruption of education is a serious risk for vulnerable children. Educational consistency is a stabilizer for children in uncertain times, and teachers play critical roles in keeping disadvantaged children on track. Schools give structure and focus amidst disruption; many studies show that disasters interrupt children’s education, leading to unfulfilled lives, as well as a loss of human capital to society. UNESCO estimates that 91% of the world’s students are currently affected by school closures. While many schools are shifting to online education, the approaches are ad hoc and unstudied. Digital access is not available to everyone, though schools are struggling to provide students with internet hotspots. Some schools report that large numbers of students have “disappeared,” i.e., fewer than one half are engaging in online courses.

American Stock Archive, Getty Images

During the Great Depression, schools reduced their hours or closed. A million children lost access to school, and a quarter of a million children hit the road and rails, becoming “drifters” in search of work. For the first time, the federal government was spurred to take an interest in children’s well-being, because it was afraid that large numbers of disaffected youth could be susceptible to a rise of authoritarianism, similar to what was happening in Europe. The New Deal launched the first free school lunch program, free nursery schools, the first federally funded work-study programs, and the National Youth Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, which employed over seven million young people. The schools were funded to reopen, and Aid to Families with Dependent Children helped poor families. The government ended child labor and raised the mandatory school attendance age to 16 in order to eliminate having children compete with adults for jobs. The first safety net for children and families was cast, and the word “teenager” entered the vocabulary for the first time.

Photo Dorothea Lange, Getty Images

On the other end of the economic spectrum, affluent families that tend toward “overparenting” can be at risk for fostering anxiety, as they strive to perfectly recreate the school learning environment at home in order to keep up with standardized testing and the college admissions cycle. These families might benefit from broadening their definition of learning to focus on simply reading, problem-solving, communication, and social and emotional skills.

“When children are involved in things they’re really interested in, a project or an exploration, they will be learning. Everything around them is a learning experience. Parents should think about how to take advantage of that,” advises Linda Darling-Hammond, professor at Stanford University Graduate School of Education and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute.

Takeaway: Vulnerable and disadvantaged families, especially with multiple stressors, should have access to and seek help from mental health and legal services. Local schools and each states’ Department of Education list educational guidance and resources for students and families. Staying connected to education is especially critical for children with any kind of disadvantage, while families who tend toward overparenting may benefit from dialing down excessive traditional educational demands.

A higher calling

Many studies of resilience find that survivors who do well have philosophies or spiritual traditions through which they interpret events and derive hope and optimism. Ann Masten, professor at the Institute for Child Development at the University of Minnesota, is a noted theoretician in the study of children’s resilience. In her book, Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development, she writes that many faith traditions—including Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—naturally incorporate all of the ingredients for resilience. They offer parenting guidance; identify moral conduct; provide role models, mentors, and community support; teach and practice self-regulation; and value the greater good. A connection to some definition of the divine and a philosophical framework help survivors make meaning of their experience and in the process, help them keep calm. Studies show that some homeless families in shelters persevere because of their faith. African American communities find connection, spiritual guidance and a coherent vision through their churches; and orphans in war-torn Sri Lanka find acceptance and peace through Buddhist and Christian practices of meditating, storytelling, and reading scripture.

Sometimes, cultural practices offer meaningful support. A study of 1000 Afghani adolescents showed that in prolonged periods of armed conflict, Afghani cultural values of faith, family unity, service, effort, morals, and honor shored up resilience. Werner’s longitudinal research in Kauai showed that many adults who eventually created happy lives drew from their cultural heritage, becoming involved in Hawaiian conservation efforts, going to the ocean in times of trouble, or caring for their elders.

Recent psychological work suggests that having a sense of purpose may be enough to get you through. Surviving, ensuring your child’s well-being, volunteering, keeping your job, or finding awe in the moment may just be enough for now.

Takeaway: A connection to something greater than ourselves—whether it’s a spiritual practice, cultural beliefs, or a sense of purpose—can help families and children orient their thoughts, feelings, and actions. Participating in a larger flow can feel supportive and calming. Children, even very young ones, enjoy and benefit from these kinds of feelings and experiences.

* * * * *

Children are neither inherently resilient nor vulnerable. Instead, their well-being arises out of who they are as individuals together with the cascades of experiences they have. Some children may luck into a combination of resources that set them on a good path early on. But even for children who don’t do well initially, studies of the life course show that many can still find happiness later in life from a new opportunity, education, a good relationship, or a fulfilling career.[5]

For now, the world is in a difficult state of uncertainty. We don’t know how long we’ll be sheltering in place, the course of the virus, or what kind of “normal” life we will return to. But the enduring lessons for our children will surely be the emotional ones. These are the lessons they will remember as adults when they inevitably experience upheaval again—only then, it may be without us. So let’s stay focused on, and grateful for, what really matters.

SEE ALSO:

Esther Perel webinars on relationships in quarantine: “The Art of Us: Love, Loss, Loneliness, and a Pinch of Humor Under Lockdown.”

Making a Family Charter by Marc Brackett (“Emotions at Home: How Do We Want to Feel?”)

Supportive Relationships and Active Skill-Building Strengthen the Foundations of Resilience Working Paper 13 from the Center on the Developing Child.

Child Mind Institute: Supporting Families During Covid-19. https://childmind.org/coping-during-covid-19-resources-for-parents/

Defending the Early Years: Covid-19 Resources

Risks and resources for LGBTQ families

[1] Werner, E. (2000). Through The Eyes of Innocents: Children Witness World War II. Basic Books, p. 1

[2] Freud, A. & Burlingham, D. (1943). War and Children. Medical War Books, p. 21.

[3] Ibid, p. 34

[4] Werner, E. (1995). Pioneer Children on the Journey West. Westview Press, p. 163.

[5] Elder, G. (1999). Children of the Great Depression: Social Change in Life Experience. Westview Press.