My most exhausting parenting memories have to do with being unable to soothe a crying baby. My husband and I had two children three years apart, on our own, thousands of miles away from our families. We were both in the startup phases of our careers, and so we took turns: We swaddled the babies, walked the hallway, put them on the dryer, swayed to music, drove in the car, used pacifiers, sat in a steamy bathroom, and rocked in the rocking chair. For a couple of years, I was so tired, I could hardly string complex sentences together at work.

New parents know this drill. And there are two big questions that arise pretty quickly: “How do you get it to stop?” and “When can we start letting the baby ‘cry it out’?”

My own childhood was not a great guide. I grew up in a time and place where the attitude toward crying even among normal parents could be summed up by the dictum, “Quit your crying,” and “I’ll give you something to cry about.” I wanted to take a different path.

Developmental science, though, was a good guide:

photo credit: depositphotos.com

Crying in the first three months of life

In 1972, Johns Hopkins University researchers Sylvia Bell and Mary Ainsworth conducted a groundbreaking—and now classic— study on infant crying. For two-to-four hours at regular intervals across the first year of life, they went into the homes of 26 mother-infant pairs and took continuous notes on baby-mother interactions. What they found was important news: Babies whose mothers responded consistently and promptly to their babies’ cries in the first three months of life cried less often and for shorter duration in the subsequent months.

These responded-to babies also transitioned more quickly to other, non-crying modes of communication, like facial expressions, gestures, and vocalizations, later in the first year. (A more recent review of studies of infant crying linked less crying to better language skills.)

What about the babies whose mothers didn’t respond to their cries? Some mothers believed that if they responded, their babies would be encouraged to cry more, becoming more dependent and demanding—in a word, “spoiled.” This view is rooted in advice from the 1920s-‘40s from behaviorists like John B. Watson and promoted by the U.S. Children’s Bureau of Infant Care. Their opinion was that parents should have an emotionally detached, businesslike relationship with their children. An entity as powerful as the federal government advised that parents should not pick up their children between feedings, lest the baby become a “spoiled, fussy, and household tyrant” who makes a “slave of the mother.”(1) This advice was not based on scientific evidence, but extrapolated from operant conditioning and what was understood about the power of positive reinforcement. Today, nearly 100 years later, that advice has been hard to eradicate.

A predictable pattern

Babies’ cries are important signals, their only communication device in the beginning. The cries are part of a stone-age “operating system” that are designed to draw the caregiver close for protection and survival and to help manage the body, brain, and feelings at the time of greatest helplessness. Just how the caregiver responds to those signals is important for wiring up a nervous system that will be as calm, organized, and integrated as possible; in other words, it’s foundational for later growth and development.

Cries run the continuum from gentle fussing that might start quietly and build up toward discomfort, hunger, or boredom, to loud, high-pitched cries that may be followed by breath-holding that signals alarm, danger, or pain. And there is everything in between.

Babies' cries are both similar and unique. Digital acoustical cry analyses captures qualities like frequency, energy, and signal-to-noise ratio and show that a pain cry has a different pattern from other cries (it’s high-pitched, loud, and sudden, with some breath-holding). Each individual baby’s cry also has a unique “cryprint.” That cryprint is something many caregivers recognize; that is, they know their own baby’s cries from that of other babies.

Though every baby is a little different, “normal” crying in the first three months of life follows a fairly predictable pattern:

Crying tends to start up at around two weeks after birth, peak at around six weeks, and gradually decline and stabilize at around three-to-four months. The six-week peak is seen in many cultures (and even in chimpanzee babies):

Each line represents a separate study of crying. Reprinted with permission from Barr, R.G., (1990). The normal crying curve: What do we really know? Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 32 (4), 356-362.

Most young babies have a fussy period. In newborns it’s often around midnight, whereas in older babies, it’s more often in the late afternoon or early evening. Extra holding, cuddling, or swaddling can help.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, two-to-three hours of crying a day is normal for babies in the first three months of life.

Why do young babies cry?

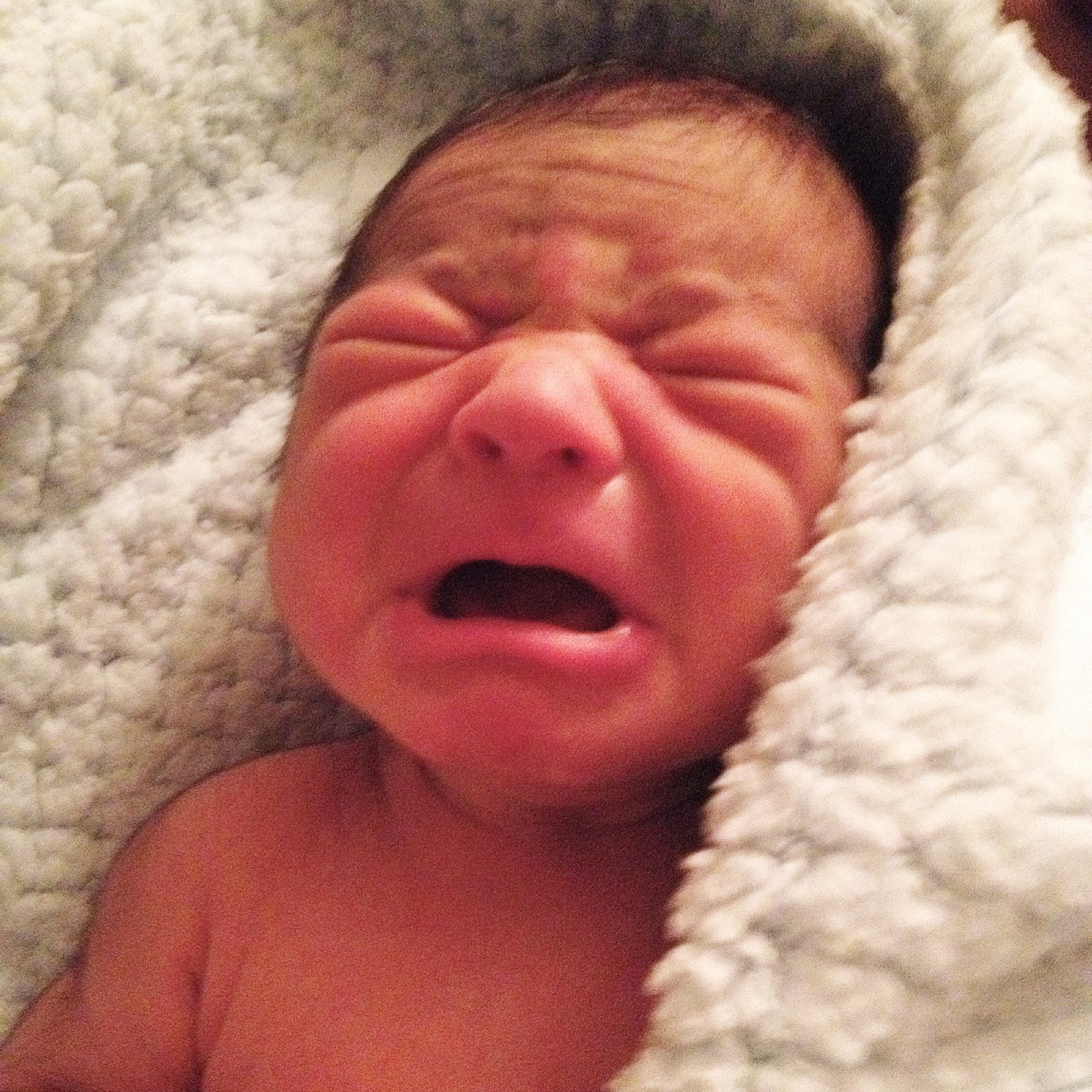

photo credit K. Merchant

Babies under three months cry for many reasons: They’re hungry, they’re uncomfortable, they’re in pain, they’re too warm or too chilly, they want more or less stimulation, they’re wet, they’re transitioning from being asleep to being awake, they don’t like a hard surface or a scratchy fabric, and the list goes on.

For an exhaustive list of possible reasons for crying, and corresponding soothing techniques, see this list at reflux.org.

In addition, some babies just cry more than others, according to pediatric psychiatrist Barry Lester of Brown University, who has seen thousands of babies in his Colic Clinic at the Brown University Center for the Study of Children at Risk. Each baby has a distinct personality and a unique temperament that, in the beginning, have little to do with parenting. Some babies are reactive and easily upset, he says, and once they get wound up it’s hard to help them calm down. On the other hand, some reactive babies are easy to soothe and may even self-quiet after their parents back off for a bit. Some babies are not particularly reactive but are still hard to soothe; so for those babies, it takes longer to trigger crying, but once they start, they’re hard to bring down.(2) And some lucky parents have babies who are just “easy”; they don’t cry much, and they’re easy to soothe when they do start.

Sometimes there is a mismatch between the baby’s needs and the parent’s ability to respond. Less experienced, first-time caregivers as well as those with less support, can easily overreact. Or caregivers may have personalities, feelings, or beliefs that get in the way of reading their baby’s signals, intentionally or unintentionally. For example, studies show that caregivers with restrictive attitudes, insufficient empathy, or a high stress response respond less well to their babies. On the other hand, too much empathy, e.g., taking on the baby’s cries as evidence of unbearable suffering, can lead to “empathic distress” in the caregiver, and in an attempt to control their own strong feelings, they might withdraw, or become overly-intrusive. Fortunate parents who’ve had positive childhood experiences—or who’ve come to terms with difficult ones—tend to find it easier to respond more sensitively to their babies’ cries.

Depressed caregivers have the hardest time responding to their babies, putting babies at greatest risk for poor outcomes. Pediatric psychiatrist Barry Lester writes that babies are highly attuned to their caregivers’ feelings, and as a result may even cry more in an unhappy environment.(3) Depression can appear in many forms, from the mild depression arising from parenting pressures and lack of sleep to full-blown, biochemical, post-partum depression. We also know that being unable to soothe a crying baby can itself trigger feelings of helplessness and depression. Sooner or later, almost every parent will break down in tears because no matter what she does, she can’t stop her baby’s crying. I remember being trapped in an airplane seat for four hours with hot tears leaking down my cheeks when I couldn’t soothe the baby in my arms. (I later learned that she had an ear infection, but there was nothing I could do in the moment except rock her gently in my arms and whisper calmly in her ear.) It is a humbling, exasperating feeling—and it’s important that parents not blame themselves, Lester urges.

Some babies cry in the first three months for no reason that professionals can understand. Psychologists and pediatricians refer to this as “endogenous” crying, meaning simply that the source is internal. Endogenous crying is uniquely human, according to Debra Zeifman, psychologist at Vassar, in her review of research studies on crying. Even our close relatives the chimpanzees stop crying when their needs are met or they’re picked up; only humans seem to have the kind of crying that can perpetuate itself regardless of the trigger.

Endogenous crying seems to resolve at around three months, when it becomes more “exogenous,” or linked reliably to external triggers. This shift from internal to external coincides with other developmental shifts, suggesting that there is a maturation of an underlying system—a “forebrain inhibitory mechanism,” or some aspect of the central nervous system—at around three months. For example, also at around the three-month mark, endogenous smiling is replaced by more social smiling, stimulated by a familiar face; newborn reflexes disappear and are replaced by more voluntary behaviors; the sleep-wake cycle settles down into a more predictable rhythm, and there are changes in EEG patterns.

And finally, in rare cases, some babies’ distinct cries (often very high-pitched or poorly phonated) may reflect underlying neurological disturbances. Scientists are working to develop acoustical cry analyses that can predict later developmental disorders such as autism.

But one important reason babies cry, Zeifman says in a vast review of studies of infant crying, may be that they have been left alone.

Holding, carrying, feeding: What’s the evidence?

Babies in Western cultures, says Zeifman, spend an exceptionally large amount of time alone compared to babies in less developed cultures. Western parents for the most part are discouraged from physical closeness and frequent feedings, and they’re often encouraged to ignore their baby’s crying. Western babies are carried an average of about 30% of their waking hours, compared to 80-90% of waking hours for babies in non-Western cultures.

Anthropologists think that continuous holding may have been a strategy to reduce infant mortality, the risk of which has been lowered dramatically in the West. Yet, practices that distance caregivers from their infants, many anthropologists and psychologists say, may contribute to more crying. In Why Is My Baby Crying?, Barry Lester points to a survey of over 180 societies that found that babies cried less when they were carried.(4)

In a randomized control study (the gold standard of studies) of supplemental holding, 99 Canadian mothers were randomly assigned to either hold their babies a minimum of three hours throughout the day (whether they were crying or not), or to a control group (where babies spent extra time in front of a mobile or abstract shape). At six weeks of age, when crying normally peaks, the extra holding had the greatest impact—reducing overall crying by 43% and nighttime crying by 51%. Extra holding made a smaller but still positive difference later, at four, eight, and twelve weeks as well.

Supplemental holding reduced crying compared to a control group. Reprinted with permission, from Hunziker, U.A. & Barr, R. G. (1986). "Increased carrying reduces infant crying: A randomized controlled trial." Pediatrics, 77 (5), 641-648.

When babies are carried, held, or worn, mothers can sense early on when something is wrong, and attend or soothe before a cry even erupts. There is no known downside full-time carrying to babies, either to their health or their psychological outcomes. Carrying and holding is, however, a lifestyle challenge in Western cultures—it is not easy for babysitters, daycare providers, or working parents to provide that extra holding to individual babies. However the benefits of it should just be more proof that we need better policies to support parents since it is unlikely that we’re going to change the way babies’ nervous systems and brains develop!

Feeding intervals also reduce crying in young babies. For example, a correlational study of two American subgroups—one from La Leche League and one control group—found that frequent feedings reduced crying in babies who were two months old but did not make a difference for four-month-old babies.

Given that more holding and more frequent feedings help the youngest babies cry less and be more comfortable, it may be possible that the amount of crying in young babies may be more flexible than we think, more amenable to care practices. If we place infants in playpens and cribs and don’t co-sleep, we may miss the early cues that babies are in distress. In Why Is My Baby Crying?, Lester goes so far as to say that Western caregiving practices actually train babies to cry. When we leave babies physically apart from caregivers until they cry, babies get the message “If you want me, call me.”(5)

Crying it out?

photo credit: K. Merchant

Some babies do defy the norm and stop crying when left to “cry it out.” In fact, a follow-up study to Bell and Ainworth’s classic 1972 work found that a few mothers who ignored their babies had babies who cried less. However, most researchers critique those findings on either methodological grounds or as a sign of “giving up” on the baby’s part—a despair and withdrawal that could ultimately lead to detachment. Modern baby gurus like pediatrician and author William Sears and psychologist Penelope Leach agree. Sears says that when caregivers let babies “cry it out,” babies can lose trust in the “signal value of the cry” and maybe even in the caregiver relationship. Leach says that leaving a baby to cry it out can activate such high levels of the stress hormone cortisol and can deplete levels of oxygen that it can be toxic to a baby’s brain. “Crying it out” also undermines the important “serve and return” interaction that is the earliest basis of cognitive development.

A 2002 report summarizes the physiological changes that can happen when babies are left to cry hard:

Heart rate rises; there can be tachycardia, i.e., racing heart. Blood pressure increases by 135%.

Oxygen levels go down.

Blood pressure in the brain becomes elevated.

Stress response is activated, with elevated levels of cortisol. If uninterrupted, this creates a cascade of effects that can eventually damage the developing brain, affect the genes that regulate stress, damage the hippocampus, and result in later problems with learning, memory, attention, and emotion regulation.

Prolonged crying can lead to aerophagia, or air-swallowing, causing pain and problems with digestion.

Energy reserves are depleted due to rapid motor movements.

White blood cell count increases with vigorous crying, suggesting the body is preparing a survival response.

What about colic or crying that won’t stop?

Estimates of colic vary, from 10% to about 20-40% of babies in Western societies. Most pediatricians diagnose colic on the Rule of Threes: crying for more than three hours a day, for more than three days a week, for more than three weeks, in a baby that is otherwise healthy. But pediatricians don’t have any solutions; they simply encourage parents to persevere until the colic runs its course, usually by around three months of age. The real risk of colic, they agree, is the stress it exacts on caregivers, placing those babies at high risk for abuse (and even shaken baby syndrome) when parents “lose it.”

As the Founder of the Colic Clinic, Barry Lester is the nation’s leading expert on colic, and he takes a strong stance. “Crying is normal,” he writes. “Colic is not. People who say that colic is normal not only are wrong; they also are doing a huge disservice to families who have colicky babies.”(6) In Why Is My Baby Crying, he defines colic as “an identifiable cry problem in the infant that is causing some impairment either in the infant or in relationships in the family.”(7)

His colic symptom checklist includes:

A sudden onset of crying—the episode seems to come out of the blue

A change in the quality of the cry (more towards pain

A change in the physical body—pulling legs up, doubling over, tightening of muscles;

The baby is inconsolable

The full checklist along with a cry “diary” can help caregivers and pediatricians problem-solve the excessive crying. Though the cause of colic is unknown, Lester has in some cases identified gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), pain, food allergies, and other sensitivities. But there is no predictable common theme, and most often, no cause can be identified. Yet families still need help, since colic can pose some developmental risk and family relationship problems due to the stress it creates.

Colicky babies are more likely to have difficult temperaments and feeding and sleeping problems, all of which can interfere with the settling of the nervous system in the first three months. Their cries and heart rates are different from those of normal babies. They are at risk for behavior problems in preschool as well as attention deficit, hyperactivity, sensory integration, and emotional reactivity.(8)

photo credit K. Merchant

Colic can take away the joy of parenting and make caregivers feel helpless and incompetent, despairing, and even angry and hateful toward the baby. It’s helpful if caregivers can know the amount of crying they can handle (their “safe cry zone,”) and what strategies they can use when their coping starts to fail—deep breathing, soft music, walking, rocking—so that they can continue to respond calmly. But when the stress rises, it’s imperative that someone else be recruited to hold the baby and give the parent some relief. This is not always possible, of course, especially for single parents, but it’s important that caregivers find some way to care for themselves as well as their babies’ crying, Lester says.

Crying in later infancy.

Crying in the first three months of life is about regulating bodily needs, wiring up the nervous system, and feeling close to and safe with a caregiver.

Crying later in infancy becomes more complex, as it’s also related to a baby’s growing cognitive and emotional capacities. The graph below shows crying data from several studies over the first two years of life.

Reprinted with permission from Barr, R.G. (1990). The normal crying curve: What do we really know? Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 32 (4), 356-362.

At around six to nine months, crying due to stranger wariness emerges. This is a normal, healthy sign that a baby understands who her “person” is, though again, different babies have different temperaments and will express more or less concern. Anthropologists think that stranger wariness served an ancient but important safety purpose of removing a baby from an incompetent or unsafe caregiver and reuniting the baby with her safe person. Very often the chosen caregiver that the baby attaches to is one specific person, even when multiple adults have cared for the baby. The baby might look at, reach for, or cry for her person when others are present, and then quiet as she is enfolded into safe arms.. But again, babies vary, and some attach just fine to multiple caregivers.

At around nine to twelve months, fear of strangers and fear of separation from a caregiver can peak crying again. This reflects a healthy cognitive growth; the baby can now anticipate the feeling of being alone, and she knows that crying is a kind of tether to the caregiver. This might especially coincide with dropping off at daycare, and skilled providers should be able to offer age-appropriate soothing.

Walking at 12-18 months can precipitate another burst of crying. As toddlers’ mobility carries them farther away from the caregiver, perhaps into a different room, they may suddenly realize that they are at sea.

Crying has another burst at around two years of age, when a baby’s growing sense of self and control over their own body meets thwarted goals and frustration. This coincides with the cognitive ability to plan action, to have deliberate wishes and intentions. As many developmental scientists say, this crying is not about the parents; it’s about the baby’s healthy growth.

How to soothe a crying baby in the first few months of life

photo credit K. Merchant

The scientific evidence is clear: Responding to a baby’s cries in the early part of life is important to the baby’s well-being, establishment of a healthy nervous system, and subsequent growth. The hard part is to figure out how! Once a baby's obvious needs are ruled out, extra holding, frequent feedings, and the skin-to-skin contact of kangaroo care go a long way toward reducing crying. Putting on your own oxygen mask first—activating your own calm response—is crucial, and so is recruiting the support of other caring adults. Ideally parenting is not a solo activity, and we are all invested in the outcome!

Here are my favorite resources for techniques on how to soothe a baby:

For a long list of options, see Coping With a Crying Infant by Jeanne Clarey Bruening.

Harvey Karp’s book, The Happiest Baby on the Block, summarizes five steps for effective soothing: swaddling, holding, making a shushing sound, gentle jiggling while supporting the head, and sucking. For a shortcut, here’s a video.

Here’s how to swaddle a baby. As I write this, a new study has linked swaddling to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). However, it’s difficult to interpret the limited results. Deaths occurred most often when babies were on their stomach, less on their sides, and least on their back, all of which is true of SIDS when babies aren’t swaddled. Caution should be taken to swaddle correctly. Follow guidelines for back sleeping, and consider other options for infants older than six months (when the risk of SIDS doubled).

Pinky McKay’s book, 100 Ways to Calm the Crying, is a compassionate, respectful collection of ideas. It will soothe just in the reading!

Barry M. Lester’s book, Why Is My Baby Crying? The Parent’s Survival Guide for Coping with Crying Problems and Colic, written with Catherine O’Neill Grace, is a reassuring read for caregivers struggling with colic. He validates that parents who have babies with crying problems deserve and need support, and he has good diagnostics and suggestions. His Colic Clinic is in Providence, RI.

Here are twelve basic reasons babies cry, and how to soothe them, from The Baby Center.

Here is a Temperament Tip Sheet to consider the range of preferences for babies of different temperaments.

Conclusion

A final thought: Babies are born in a very immature physical state, with nervous systems and brains and bodies that have a long way to go—25 years, really—until they reach maturity. Parents and caregivers have to be flexible and adaptive in supporting the child’s current developmental needs. Different kinds of responses are important at different ages. For young babies, consistent affectionate responding is about meeting their physical and psychological needs, calming and integrating the nervous system, and creating a loving and trusting foundation to the relationship.

As babies grow—one to two years old and beyond—it may not be appropriate or even possible to soothe every cry. In fact, small bits of manageable stress in the presence of a caring adult help to “inoculate” a toddler for some of life’s vicissitudes and realities. But this is a gradual on-ramp, with a supportive adult. Later, new factors become important for parents to consider, like the development of language and cognition, the neurological ability to inhibit oneself, and the scaffolding of emotional skills.

Whatever the age, a good cry can always go a long way toward letting off steam, communicating, and healing.

Notes

(1) U. S. Children's Bureau of Infant Care. Care of Children Series No. 2. Bureau Publication No. 8 (Revised), 1924. As cited by Bell, S. & Ainsworth, M. (1972). Infant crying and maternal responsiveness. Child Development, 43 (4), 1171-1190.

(2) Lester, B. with Grace, C.O. (2005). Why Is My Baby Crying? The Parent's Survival Guide for Coping with Crying Problems and Colic. NY, NY: Harper Collins, p 89.

(3) Lester, p. 73

(4) Lester, p. 88

(5) Lester, p. 92

(6) Lester, p. 1

(7) Lester, p. 69

(8) Lester, p. 58